Primary caregivers

Main Findings

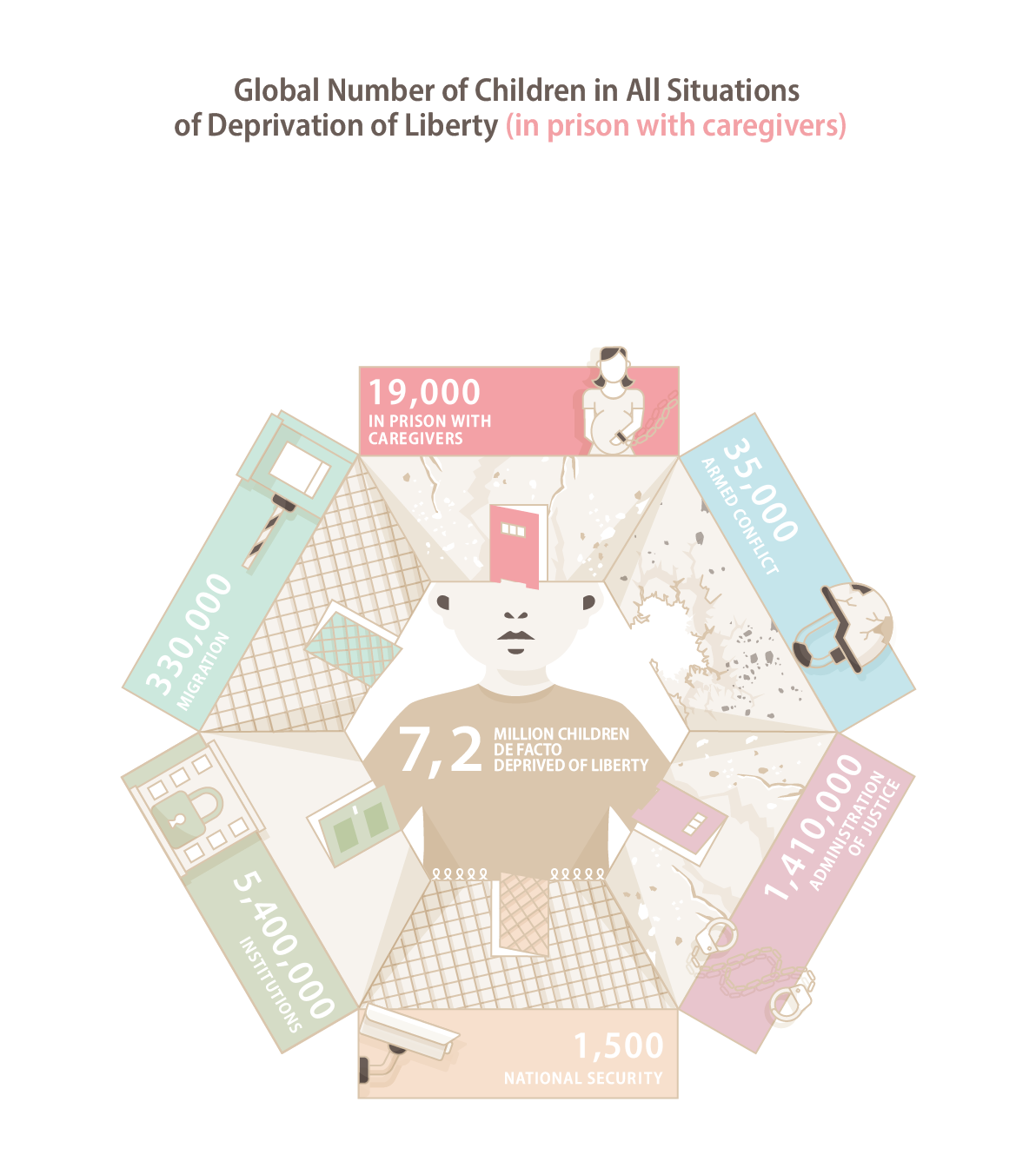

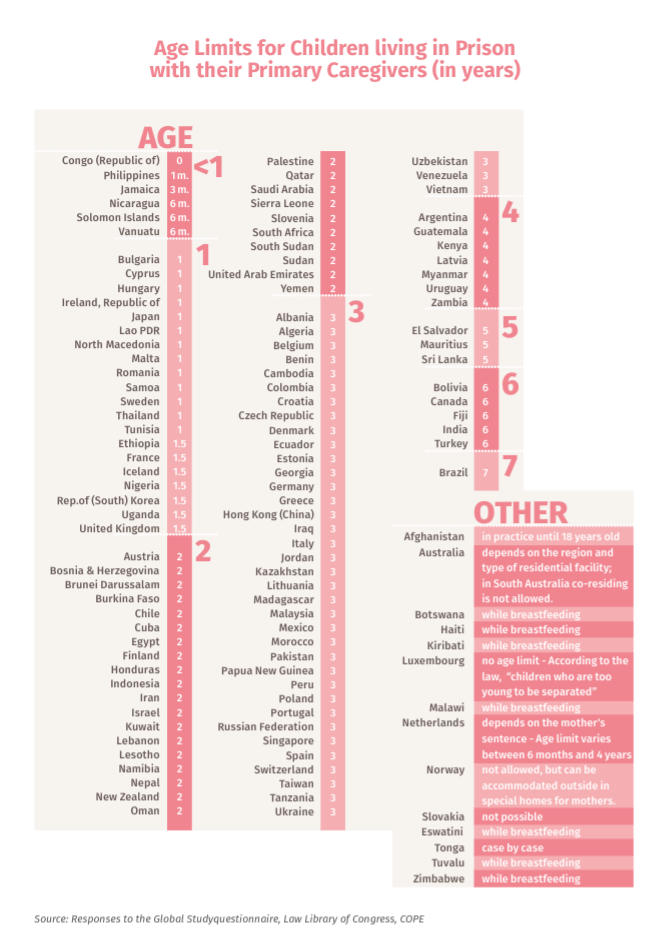

![]() Approximately 19,000 children were living with their primary caregivers in prison in 2017. While it is easier to track down numbers from some regions (South America and Europe, for example), the lack of data is evident in most other regions.

Approximately 19,000 children were living with their primary caregivers in prison in 2017. While it is easier to track down numbers from some regions (South America and Europe, for example), the lack of data is evident in most other regions.

![]() Growing up in prison has a significant adverse influence on children because of ill-suited living conditions, inadequate hygiene, a lack of stimuli, and a subset of repetitive sensorial experiences linked to the prison world (e.g. doors slamming, keys jangling and industrial smells).

Growing up in prison has a significant adverse influence on children because of ill-suited living conditions, inadequate hygiene, a lack of stimuli, and a subset of repetitive sensorial experiences linked to the prison world (e.g. doors slamming, keys jangling and industrial smells).

![]() There is also a general lack of adequate prison facilities, such as those with specific mother-child units.

There is also a general lack of adequate prison facilities, such as those with specific mother-child units.

Legal Background

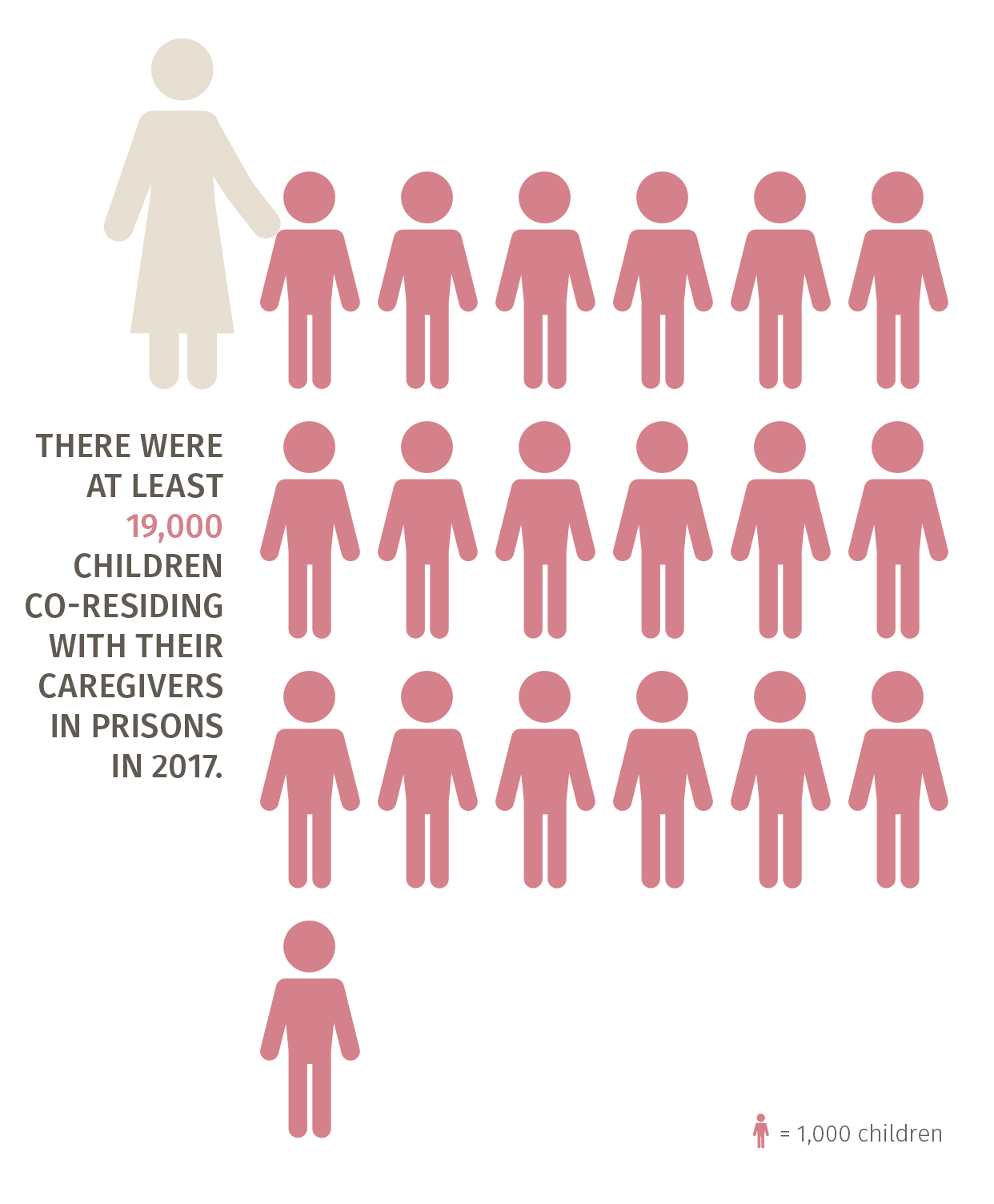

No universal standards determine whether children should be detained with a primary caregiver and under what conditions. Also, factors such as specific age limits for a child’s admission into a place of detention and restrictions on the length of permissible stay can result in the separation of child and caregiver.

The question of whether and how long children should be allowed to stay in prison with one of their parents is a complex issue with profound implications for the well-being and development of the child. Therefore, decisions throughout the criminal justice procedure must be determined on a case-by-case basis, considering: the alternative care possibilities, the availability of non-custodial measures, the suitability of existing prison facilities, the possibility of enabling safe co-residence and assessing how the separation from the primary caregiver is likely to affect the child.

The detention of a child with a primary caregiver is regulated by the following clauses of the Convention on the Rights of the Child:

![]() Article 3(1), always taking into account the best interests of the child;

Article 3(1), always taking into account the best interests of the child;

![]() Article 2(2), using non-discrimination guiding principles;

Article 2(2), using non-discrimination guiding principles;

![]() Article 6, safeguarding children’s survival and development allowing children to grow up in a healthy and protected manner;

Article 6, safeguarding children’s survival and development allowing children to grow up in a healthy and protected manner;

![]() Article 12, ensuring child participation;

Article 12, ensuring child participation;

![]() Article 9(1), ensuring the child’s right to a family environment.

Article 9(1), ensuring the child’s right to a family environment.

Other regional instruments:

![]() Article 8 of The European Convention of Human Rights;

Article 8 of The European Convention of Human Rights;

![]() Article 24 of The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union;

Article 24 of The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union;

![]() Article 19 of The Inter-American Convention of Human Rights;

Article 19 of The Inter-American Convention of Human Rights;

![]() Article 15 of The San Salvador Protocol.

Article 15 of The San Salvador Protocol.

Pathways to Detention

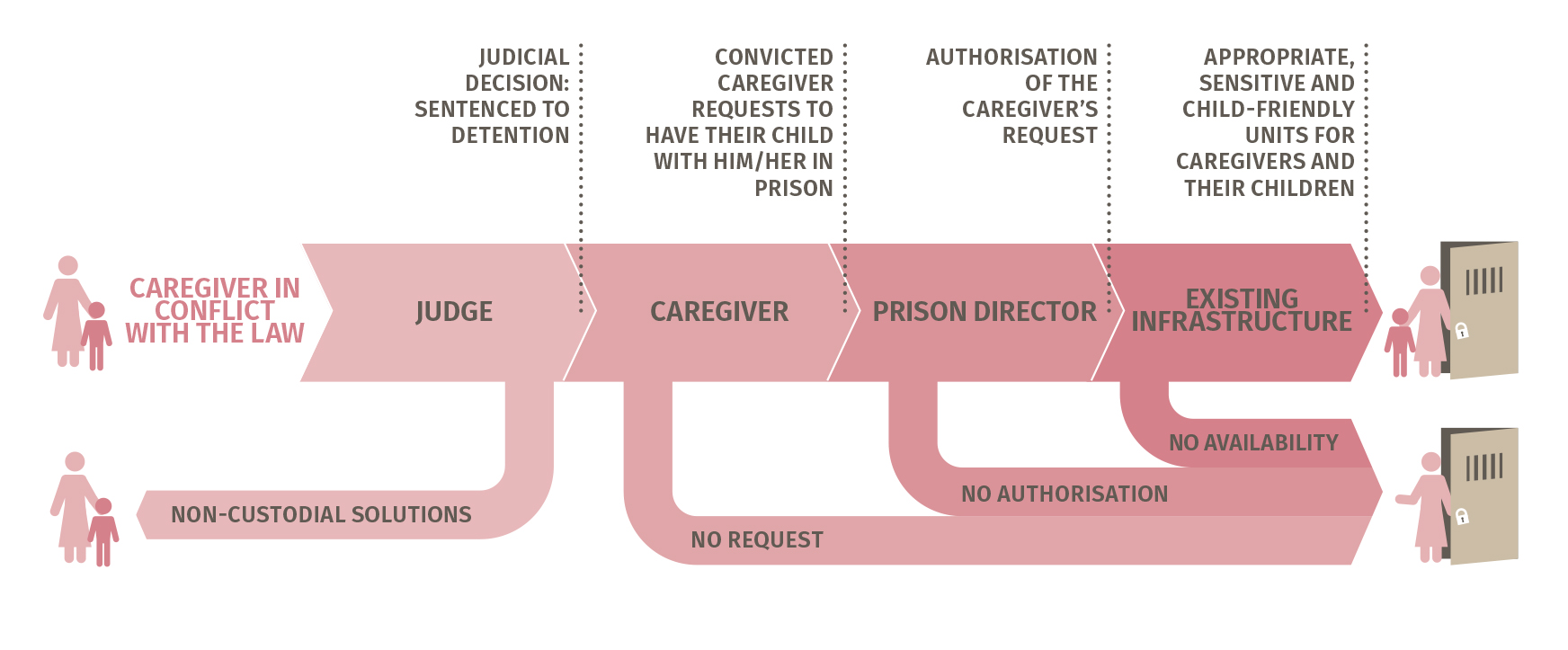

![]() Children co-residing in prisons with their primary caregiver are deprived of liberty as a consequence of decisions and actions by their primary caregivers, as well as the policy choices made by governments and the sentencing options of judges.

Children co-residing in prisons with their primary caregiver are deprived of liberty as a consequence of decisions and actions by their primary caregivers, as well as the policy choices made by governments and the sentencing options of judges.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() When sentencing a primary caregiver, courts shall recognise children as rights holders, take their best interests into consideration and avoid, as much as possible, prison sentences.

When sentencing a primary caregiver, courts shall recognise children as rights holders, take their best interests into consideration and avoid, as much as possible, prison sentences.

![]() Governments are encouraged to recognise both the detrimental impact of family separation due to parental incarceration and the detrimental impact of deprivation of liberty with a parent. A presumption against a custodial measure or sentence for primary caregivers should apply.

Governments are encouraged to recognise both the detrimental impact of family separation due to parental incarceration and the detrimental impact of deprivation of liberty with a parent. A presumption against a custodial measure or sentence for primary caregivers should apply.

![]() States shall incorporate assessments of the best interests of the child into decision-making processes, including pretrial detention decisions, sentencing decisions, and decisions regarding whether and for how long a child shall live with a primary caregiver in prison.

States shall incorporate assessments of the best interests of the child into decision-making processes, including pretrial detention decisions, sentencing decisions, and decisions regarding whether and for how long a child shall live with a primary caregiver in prison.

![]() If imprisonment is unavoidable, an individualised assessment of the best interests of the child must inform any decision about whether and when a child should accompany a primary caregiver into prison or be separated from such carer.

If imprisonment is unavoidable, an individualised assessment of the best interests of the child must inform any decision about whether and when a child should accompany a primary caregiver into prison or be separated from such carer.

![]() Adequate provisions must be made for the care of the children entering prison with their parent and age-appropriate facilities (such as nurseries, kindergartens, mother-child units, and children’s care homes) and services must be supplied to safeguard and promote the safety, dignity and development of any child living with a parent in prison. The child must be carefully protected from violence, trauma and harmful situations.

Adequate provisions must be made for the care of the children entering prison with their parent and age-appropriate facilities (such as nurseries, kindergartens, mother-child units, and children’s care homes) and services must be supplied to safeguard and promote the safety, dignity and development of any child living with a parent in prison. The child must be carefully protected from violence, trauma and harmful situations.

![]() When the child is leaving the place of detention, the primary caregivers should ideally be released together with the child.

When the child is leaving the place of detention, the primary caregivers should ideally be released together with the child.