Armed Conflict

Main Findings

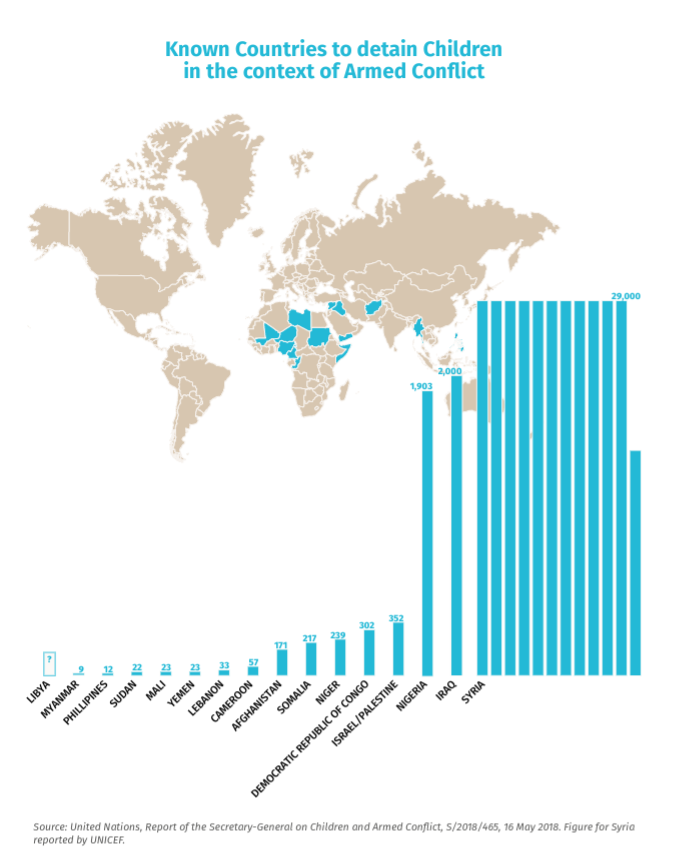

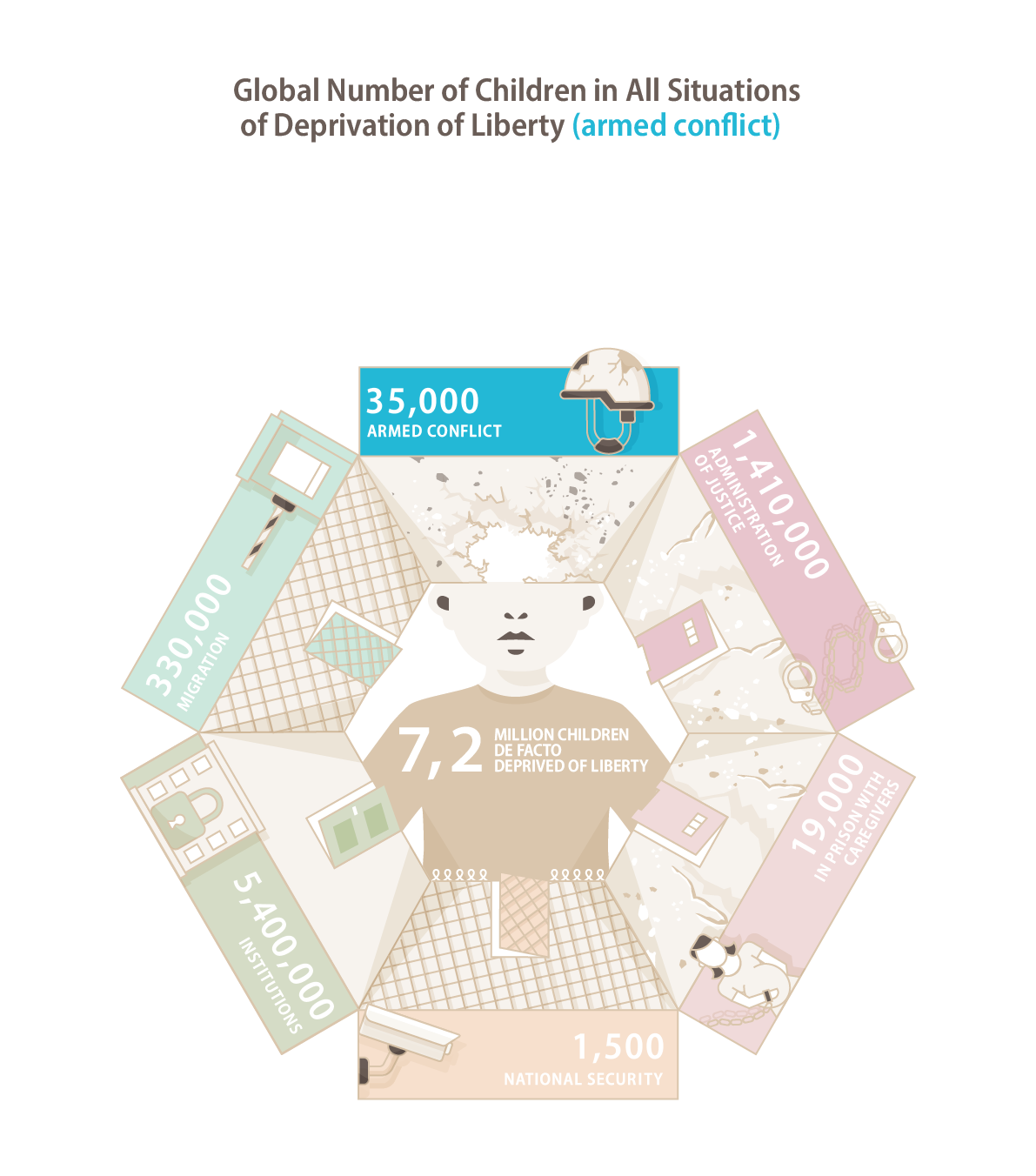

![]() More than 1 in 6 children worldwide were living in a conflict zone ib 2018. In many of these conflict areas, armed forces and armed groups recruit children to serve as combatants, guards, spies, messengers, cooks, and other roles, including sexual exploitation. Data collected for the Global Study indicates that over 35,000 children are deprived of liberty in at least 16 countries in the context of armed conflict, including an estimated 29,000 foreign children related to the Islamic State (‘ISIS’) detained in 2019 in camps in Iraq and Syria. Other countries with conflict situations with the highest numbers of detained children are Syria, Nigeria, Iraq, Israel, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia. The actual number is likely to be considerably higher, considering undocumented cases in internally displaced people (IDP) camps, military and intelligence facilities, and makeshift detention centres.

More than 1 in 6 children worldwide were living in a conflict zone ib 2018. In many of these conflict areas, armed forces and armed groups recruit children to serve as combatants, guards, spies, messengers, cooks, and other roles, including sexual exploitation. Data collected for the Global Study indicates that over 35,000 children are deprived of liberty in at least 16 countries in the context of armed conflict, including an estimated 29,000 foreign children related to the Islamic State (‘ISIS’) detained in 2019 in camps in Iraq and Syria. Other countries with conflict situations with the highest numbers of detained children are Syria, Nigeria, Iraq, Israel, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia. The actual number is likely to be considerably higher, considering undocumented cases in internally displaced people (IDP) camps, military and intelligence facilities, and makeshift detention centres.

![]() Children detained in the context of armed conflict often find themselves doubly victimized and subjected to violence. First, by armed groups illegally exploiting them, and then, State authorities or opposing armed actors detaining them for their association with those same groups, in many cases subjecting them to torture or ill-treatment to extract confessions, gather intelligence, or as punishment.

Children detained in the context of armed conflict often find themselves doubly victimized and subjected to violence. First, by armed groups illegally exploiting them, and then, State authorities or opposing armed actors detaining them for their association with those same groups, in many cases subjecting them to torture or ill-treatment to extract confessions, gather intelligence, or as punishment.

![]() Overall, detention conditions are often deplorable, with severe overcrowding and lack of sanitation, food, and health care, leading to children dying due to neglect or ill-treatment in custody.

Overall, detention conditions are often deplorable, with severe overcrowding and lack of sanitation, food, and health care, leading to children dying due to neglect or ill-treatment in custody.

Legal Background

International law prohibits the use of children in direct hostilities and any recruitment of children by non-State armed groups. International child justice standards recognise children involved in armed conflict primarily as victims of grave violations of their human rights, not as perpetrators.

Detention should be prevented, save in exceptional cases where children may have committed serious offenses or pose a serious threat to a State’s security, and only under due process and international child justice standards. In particular, children should not be detained solely for membership in an armed group.

![]() Since 1999, the UN Security Council has adopted a series of resolutions on children and armed conflict that call on Member States to ensure the rehabilitation and reintegration of children recruited in violation of international law. These include resolutions 1261 (1999), 1314 (2000), 1379 (2001), 1460 (2003), 1539 (2004), 1612 (2005), 1882 (2009), 1998 (2011), 2225 (2015), and 2427 (2018).

Since 1999, the UN Security Council has adopted a series of resolutions on children and armed conflict that call on Member States to ensure the rehabilitation and reintegration of children recruited in violation of international law. These include resolutions 1261 (1999), 1314 (2000), 1379 (2001), 1460 (2003), 1539 (2004), 1612 (2005), 1882 (2009), 1998 (2011), 2225 (2015), and 2427 (2018).

![]() Resolution 2427 addresses detention specifically, emphasising that no child should be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily and calling on all parties to conflict to cease unlawful or arbitrary detention as well as torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment imposed on children during their detention. It encourages States to establish ’standard operating procedures for the rapid handover of these children to relevant civilian child protection actors‘ and to consider non judicial measures as alternatives to prosecution and detention that focus on the rehabilitation and reintegration for children formerly associated with armed forces and armed groups.

Resolution 2427 addresses detention specifically, emphasising that no child should be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily and calling on all parties to conflict to cease unlawful or arbitrary detention as well as torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment imposed on children during their detention. It encourages States to establish ’standard operating procedures for the rapid handover of these children to relevant civilian child protection actors‘ and to consider non judicial measures as alternatives to prosecution and detention that focus on the rehabilitation and reintegration for children formerly associated with armed forces and armed groups.

Pathways to Detention

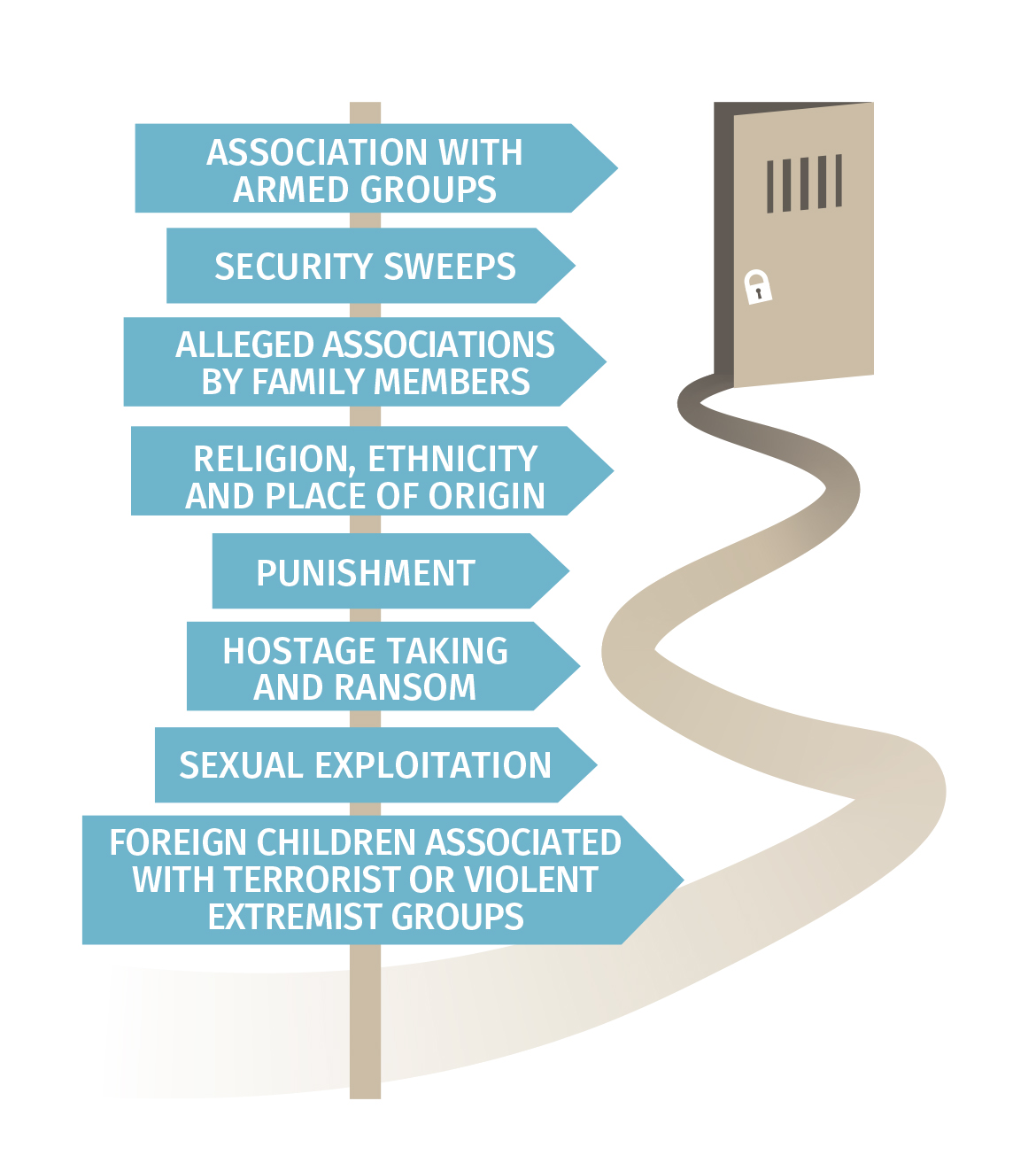

![]() Some Middle Eastern, West and East African States criminalise mere association with non-state armed groups, even if no other crime has been committed.

Some Middle Eastern, West and East African States criminalise mere association with non-state armed groups, even if no other crime has been committed.

![]() Some children who have been recruited across borders by non-State armed groups have been detained and prosecuted upon return to their home countries – for alleged involvement of family members with such groups; for being of seemingly fighting age, belonging to a certain religion or ethnicity, originating from a region where armed groups are active.

Some children who have been recruited across borders by non-State armed groups have been detained and prosecuted upon return to their home countries – for alleged involvement of family members with such groups; for being of seemingly fighting age, belonging to a certain religion or ethnicity, originating from a region where armed groups are active.

![]() Armed groups and terrorist organisations also detain children for various reason, such as recruitment purposes, extracting ransom, sexual exploitation or as bargaining chips for prisoner exchanges.

Armed groups and terrorist organisations also detain children for various reason, such as recruitment purposes, extracting ransom, sexual exploitation or as bargaining chips for prisoner exchanges.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() In line with UN Security Council Resolution 2427 (2018), States should recognise that children who were detained for association with armed groups are first and foremost victims of grave abuses of human rights and international humanitarian law and prioritise their recovery and reintegration.

In line with UN Security Council Resolution 2427 (2018), States should recognise that children who were detained for association with armed groups are first and foremost victims of grave abuses of human rights and international humanitarian law and prioritise their recovery and reintegration.

![]() States should not detain, prosecute, or punish children who have been associated with armed forces or armed groups solely for their membership in such forces or groups.

States should not detain, prosecute, or punish children who have been associated with armed forces or armed groups solely for their membership in such forces or groups.

![]() States should adopt and implement standard operating procedures for the immediate and direct handover of children from military custody to appropriate child protection agencies.

States should adopt and implement standard operating procedures for the immediate and direct handover of children from military custody to appropriate child protection agencies.

![]() States should ensure that children formerly associated with armed forces and armed groups are provided with appropriate rehabilitation and reintegration assistance, and where possible and in the best interests of the child, family reunification.

States should ensure that children formerly associated with armed forces and armed groups are provided with appropriate rehabilitation and reintegration assistance, and where possible and in the best interests of the child, family reunification.

![]() States and other parties to an armed conflict must not detain children illegally or arbitrarily, including for preventive purposes; alleged offences by family members; intelligence-gathering; purposes of ransom, prisoner swaps, as leverage in negotiations; or for sexual exploitation.

States and other parties to an armed conflict must not detain children illegally or arbitrarily, including for preventive purposes; alleged offences by family members; intelligence-gathering; purposes of ransom, prisoner swaps, as leverage in negotiations; or for sexual exploitation.

![]() States should ensure that any arrest or detention of a child should be based on specific and credible evidence of criminal activity and prioritise diversion from the criminal justice system.

States should ensure that any arrest or detention of a child should be based on specific and credible evidence of criminal activity and prioritise diversion from the criminal justice system.

![]() States should take responsibility for children abroad who are their citizens and who may be detained on security related offences or for association with armed groups, including children born to their nationals.

States should take responsibility for children abroad who are their citizens and who may be detained on security related offences or for association with armed groups, including children born to their nationals.