Institutions

Main Findings

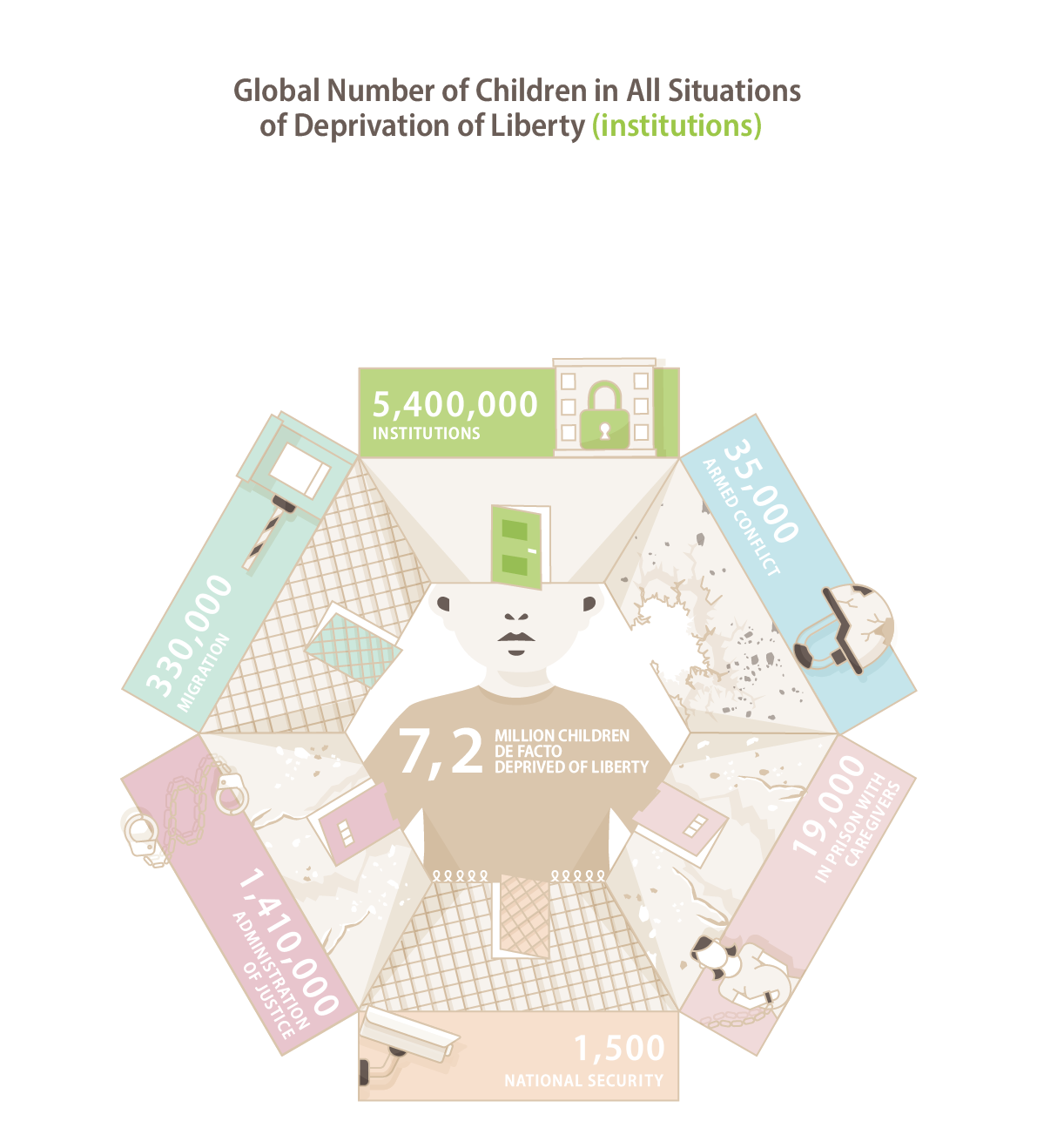

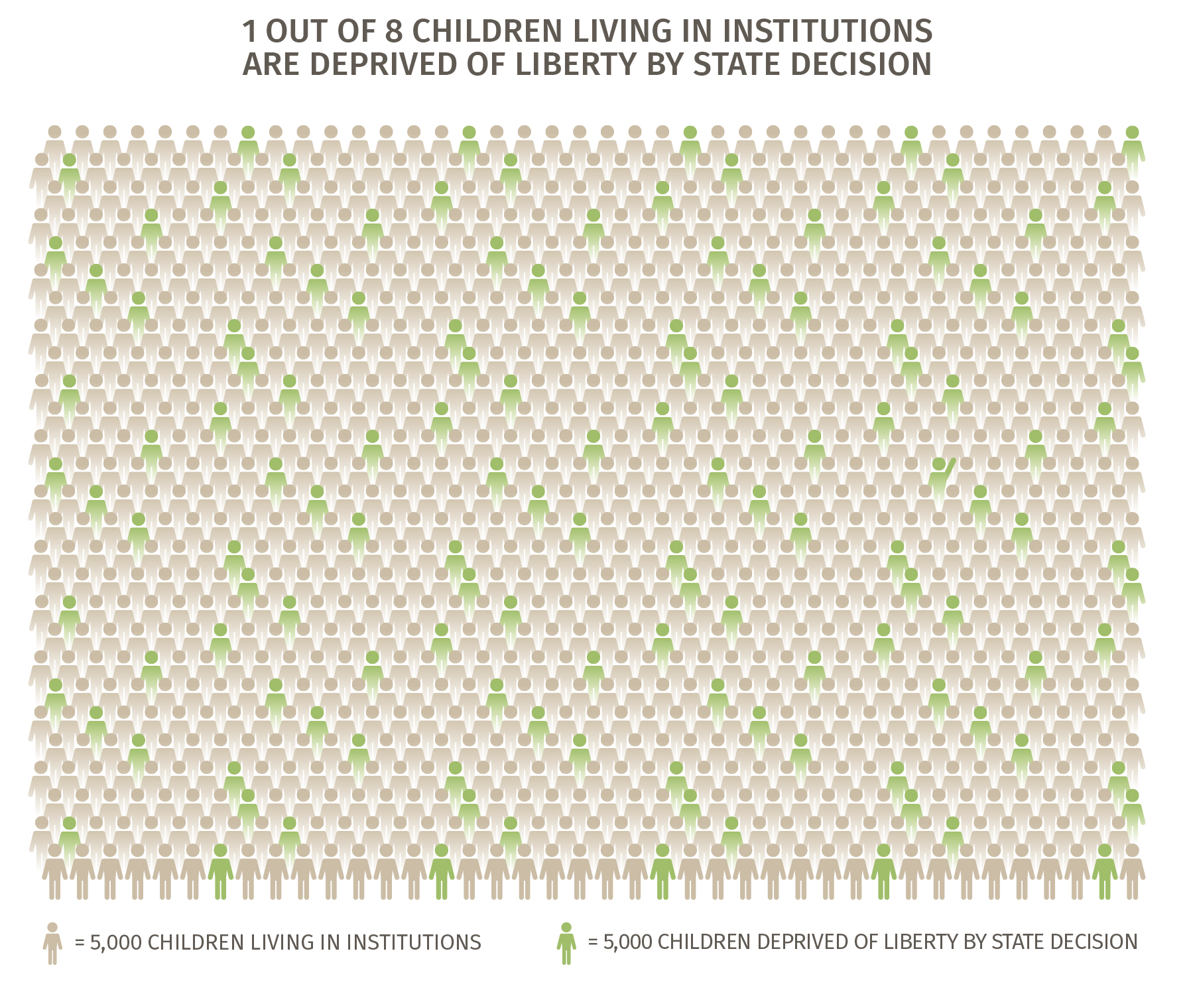

![]() At least 5.4 million children live in institutions worldwide. This fate can easily be avoided as these children could v be reunited with their parents and primary caregivers or live in a family-based setting given the right support. These children are separated from their families and deprived of their liberty in institutions for various reasons. Contrary to popular belief, 80% of children in orphanages have at least one living parent. Effects of child separation and institutionalisation are grave and may last a lifetime. Being largely invisible, such children are particularly vulnerable to violence, neglect and abuse.

At least 5.4 million children live in institutions worldwide. This fate can easily be avoided as these children could v be reunited with their parents and primary caregivers or live in a family-based setting given the right support. These children are separated from their families and deprived of their liberty in institutions for various reasons. Contrary to popular belief, 80% of children in orphanages have at least one living parent. Effects of child separation and institutionalisation are grave and may last a lifetime. Being largely invisible, such children are particularly vulnerable to violence, neglect and abuse.

![]() Institutions, by their very nature, are unable to operate without depriving children of their liberty: physical restraints, isolation and solitary confinement occur in some institutions, which are particularly egregious examples of deprivation of liberty, in some instances amounting to torture or ill-treatment. In addition, unregistered, privately run institutions often receive children through informal referrals and, in some cases, result in exploitation through commodifying care or trafficking of children. Moreover, violence within institutions has been identified in countries across the globe. Occurrences range from physical and psychological abuse in the guise of ‘corrective actions’, to sexual violence against girls with disabilities and inappropriate use of psychotropic medication. In some cases, children experience serious neglect, including denial of healthcare and adequate nutrition. Sometimes, the lack of State funding results in fundraising strategies severely harming children, such as keeping children in a state of poverty or malnourished to attract more donations or trafficking children for sexual exploitation.

Institutions, by their very nature, are unable to operate without depriving children of their liberty: physical restraints, isolation and solitary confinement occur in some institutions, which are particularly egregious examples of deprivation of liberty, in some instances amounting to torture or ill-treatment. In addition, unregistered, privately run institutions often receive children through informal referrals and, in some cases, result in exploitation through commodifying care or trafficking of children. Moreover, violence within institutions has been identified in countries across the globe. Occurrences range from physical and psychological abuse in the guise of ‘corrective actions’, to sexual violence against girls with disabilities and inappropriate use of psychotropic medication. In some cases, children experience serious neglect, including denial of healthcare and adequate nutrition. Sometimes, the lack of State funding results in fundraising strategies severely harming children, such as keeping children in a state of poverty or malnourished to attract more donations or trafficking children for sexual exploitation.

Legal Background

![]() States must ensure that no children are separated from their parents against their will, except where such separation is necessary to safeguard the best interests of the child. Importantly, in line with Article 23 CRPD, children should never be separated from their parents on the basis of their disability or the disability of their parents.

States must ensure that no children are separated from their parents against their will, except where such separation is necessary to safeguard the best interests of the child. Importantly, in line with Article 23 CRPD, children should never be separated from their parents on the basis of their disability or the disability of their parents.

![]() For children who are unable to live with their parents or cannot remain in that environment due to risks, States are obliged under Article 20 CRC to ensure suitable alternative care options (i.e. specifically appropriate, necessary and constructive for the child’s best interests), such as foster placement, Kafalah under Islamic Law, or adoption.

For children who are unable to live with their parents or cannot remain in that environment due to risks, States are obliged under Article 20 CRC to ensure suitable alternative care options (i.e. specifically appropriate, necessary and constructive for the child’s best interests), such as foster placement, Kafalah under Islamic Law, or adoption.

![]() Placing children in institutions to deliver support or services is disproportionate. It will hardly ever meet the high standards of a measure of last resort in Article 37(b) CRC.

Placing children in institutions to deliver support or services is disproportionate. It will hardly ever meet the high standards of a measure of last resort in Article 37(b) CRC.

![]() Once in alternative care, in accordance with Article 6 CRC, States should provide children with the emotional support, education and programmes needed for healthy development, including established standards relating to safety, education, healthcare, nutrition, privacy, leisure activities, contact with family, etc.

Once in alternative care, in accordance with Article 6 CRC, States should provide children with the emotional support, education and programmes needed for healthy development, including established standards relating to safety, education, healthcare, nutrition, privacy, leisure activities, contact with family, etc.

Pathways to Detention

Children are placed in institutions by their parents or other caregivers, often on the advice or insistence of governmental authorities or at least with their knowledge and acquiescence. There are, however, also cases in which children, including children with disabilities, are placed in private institutions without the knowledge or acquiescence of governmental authorities.

![]() POVERTY

POVERTY

Poor economic conditions are one of the root causes leading to institutionalisation of children, with some States being more likely to place children in institutions than to provide family support. Poverty, and neglect based on poverty, is an inadequate justification to separate children from their families and deprive them of their liberty.

![]() DISABILITY

DISABILITY

Children with disabilities tend to be over-represented in care institutions. Stigmatisation, lack of State support for parents, lack of caregiving capacity of families, misdiagnosis, and an exclusive focus on the medical model of disability lead to the overuse of institutionalisation.

![]() BELONGING TO AN ETHNIC MINORITY

BELONGING TO AN ETHNIC MINORITY

Indigenous children and children belonging to ethnic minorities are also significantly overrepresented in care and justice systems, such as Roma children in Central and Eastern Europe.

![]() VIOLENCE IN THE FAMILY

VIOLENCE IN THE FAMILY

Experiencing violence in the family, including neglect and psychological, physical and sexual violence, is often a primary cause for children to be placed in institutions.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() States are urged to consciously and actively target the identified causes of children being separated from their families and provide the necessary measures to prevent this through support for families and strengthened child protection and social support systems.

States are urged to consciously and actively target the identified causes of children being separated from their families and provide the necessary measures to prevent this through support for families and strengthened child protection and social support systems.

![]() States are urged to develop and implement a strategy for progressive deinstitutionalisation that includes significant investments in family and community-based support and services.

States are urged to develop and implement a strategy for progressive deinstitutionalisation that includes significant investments in family and community-based support and services.

![]() States should prioritise a process to assess children presently in institutions and make all efforts to return them safely to their immediate family, extended family, or into other families through foster care, Kafalah or adoption.

States should prioritise a process to assess children presently in institutions and make all efforts to return them safely to their immediate family, extended family, or into other families through foster care, Kafalah or adoption.

![]() While prevention and deinstitutionalisation are being carried out, States should ensure that all alternative care options respect the rights of all children and implement measures that guarantee the full participation of all children, including children with disabilities.

While prevention and deinstitutionalisation are being carried out, States should ensure that all alternative care options respect the rights of all children and implement measures that guarantee the full participation of all children, including children with disabilities.

![]() States are also urged to map all institutions within the country, whether private or public, whether presently registered or not, and, regardless of how children arrived there, conduct an independent review of each institution. States should operationalise a system of registration, licensing, regulation and inspection.

States are also urged to map all institutions within the country, whether private or public, whether presently registered or not, and, regardless of how children arrived there, conduct an independent review of each institution. States should operationalise a system of registration, licensing, regulation and inspection.

![]() States should take immediate measures to stop the exploitation of children through orphan tourism, and use children as a commodity to run institutions as a business.

States should take immediate measures to stop the exploitation of children through orphan tourism, and use children as a commodity to run institutions as a business.

![]() States are further encouraged to ensure that children being placed in hospitals, psychiatric facilities and rehabilitation (including substance abuse) centres are properly counted and are included in systemic transformation and deinstitutionalisation efforts.

States are further encouraged to ensure that children being placed in hospitals, psychiatric facilities and rehabilitation (including substance abuse) centres are properly counted and are included in systemic transformation and deinstitutionalisation efforts.