National security

Main Findings

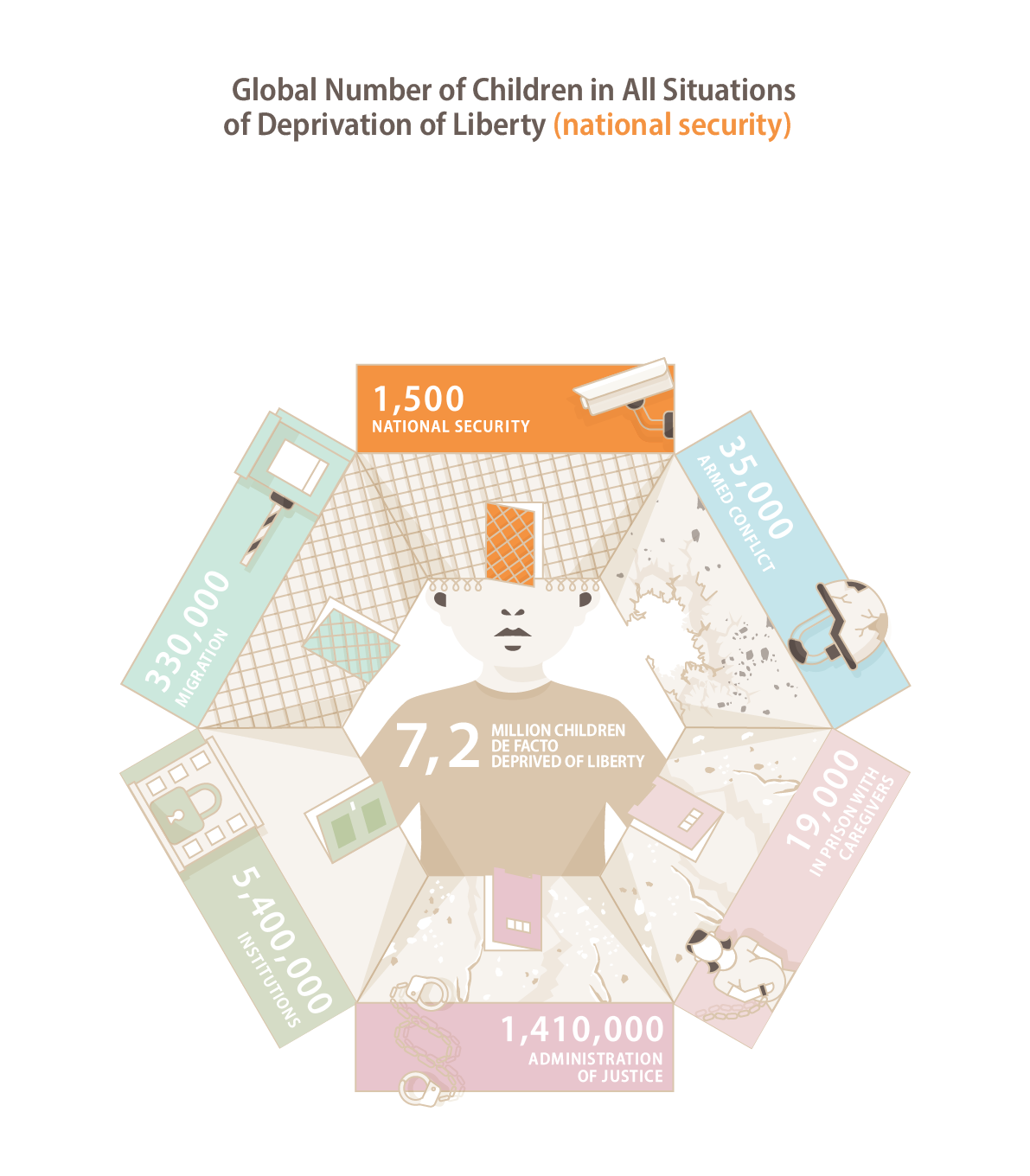

![]() In 31 countries, children have been detained in the context of national security in 2019. At least 1,500 children are detained in the context of national security in countries without conflicts on their own territories.

In 31 countries, children have been detained in the context of national security in 2019. At least 1,500 children are detained in the context of national security in countries without conflicts on their own territories.

![]() Armed groups designated as terrorist or armed groups termed violent extremist have recruited thousands of children, in some cases across borders, to carry out suicide and other attacks, and for various support roles both within and outside the theatre of hostilities. Some are recruited through force, coercion or deception, while others are influenced by family and peer networks, poverty, physical insecurity, social exclusion, financial incentives, or a search for identity or status. The growth of the internet has provided such groups with new avenues to recruit children, who are often particularly susceptible to propaganda and online exploitation due to their age and relative immaturity.

Armed groups designated as terrorist or armed groups termed violent extremist have recruited thousands of children, in some cases across borders, to carry out suicide and other attacks, and for various support roles both within and outside the theatre of hostilities. Some are recruited through force, coercion or deception, while others are influenced by family and peer networks, poverty, physical insecurity, social exclusion, financial incentives, or a search for identity or status. The growth of the internet has provided such groups with new avenues to recruit children, who are often particularly susceptible to propaganda and online exploitation due to their age and relative immaturity.

Legal Background

Counter-terrorism laws often fail to distinguish between adults and children, include overly broad definitions of terrorism, provide fewer procedural guarantees, and impose harsher penalties, which lead to 1,500 children detained on national security grounds in non-conflict countries. Some States even criminalise mere association with non-State armed groups designated as terrorist or armed groups termed violent extremist and have extended the period of time that individuals can be detained without charge or before trial, lowered the age of detention for certain offences, and required children charged with national security offences to be tried in adult courts or before military tribunals.

Although some international human rights treaties allow derogation during times of public emergency, the CRC does not contain an explicit derogation clause and allows only very narrow limitations to its provisions.

![]() Thus, the key provisions of the CRC that are applicable to the right to personal liberty (Article 37) and the administration of justice (Article 40) also apply to any child who may have committed national security or terrorism-related offenses. Most importantly, deprivation of liberty shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

Thus, the key provisions of the CRC that are applicable to the right to personal liberty (Article 37) and the administration of justice (Article 40) also apply to any child who may have committed national security or terrorism-related offenses. Most importantly, deprivation of liberty shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

Pathways to Detention

![]() Children are detained for mere alleged association with non-State armed groups designated as terrorist or violent extremist, a worrisome development as the Internet has provided such groups with new avenues to recruit children, who are often particularly susceptible to propaganda and online exploitation.

Children are detained for mere alleged association with non-State armed groups designated as terrorist or violent extremist, a worrisome development as the Internet has provided such groups with new avenues to recruit children, who are often particularly susceptible to propaganda and online exploitation.

![]() Although the recruitment of children into non-State armed groups, including these designated terrorist or violent extremist, is unlawful, counter-terrorism legislation often treats children as perpetrators rather than victims, expressing a complete disregard for the conditions, forcing them into illegal recruitment.

Although the recruitment of children into non-State armed groups, including these designated terrorist or violent extremist, is unlawful, counter-terrorism legislation often treats children as perpetrators rather than victims, expressing a complete disregard for the conditions, forcing them into illegal recruitment.

![]() New legislation based on overly broad definitions of terrorism is also used to detain children for a wide range of activities outside of national security concerns, such as participation in peaceful protests, involvement in banned political groups or alleged gang activity. Following their arrest, children have been detained without charge or trial for years and, when convicted, often by adult or military courts, have sometimes received harsh sentences, including the death penalty.

New legislation based on overly broad definitions of terrorism is also used to detain children for a wide range of activities outside of national security concerns, such as participation in peaceful protests, involvement in banned political groups or alleged gang activity. Following their arrest, children have been detained without charge or trial for years and, when convicted, often by adult or military courts, have sometimes received harsh sentences, including the death penalty.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() In line with UN Security Council Resolution 2427 (2018), States should recognise that children recruited by non-State armed groups designated as terrorist or armed groups termed violent extremist are first and foremost victims of grave abuses of human rights.

In line with UN Security Council Resolution 2427 (2018), States should recognise that children recruited by non-State armed groups designated as terrorist or armed groups termed violent extremist are first and foremost victims of grave abuses of human rights.

![]() States should explicitly exclude children from national counter-terrorism and security legislation, and ensure that children suspected of national security offences are treated exclusively within child justice systems, with full child justice guarantees, including access to counsel, the right to challenge their confinement, protection of privacy, and contact with their families.

States should explicitly exclude children from national counter-terrorism and security legislation, and ensure that children suspected of national security offences are treated exclusively within child justice systems, with full child justice guarantees, including access to counsel, the right to challenge their confinement, protection of privacy, and contact with their families.

![]() States should ensure that counter-terrorism legislation with penal sanctions is never used against children peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, freedom of religion or belief, or freedom of association and assembly.

States should ensure that counter-terrorism legislation with penal sanctions is never used against children peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, freedom of religion or belief, or freedom of association and assembly.

![]() States should end all administrative or preventive detention of children and instead develop alternatives to deprivation of liberty, including diversion programmes, care, guidance and supervision orders, counseling, probation, foster care, education and vocational training programmes, and other non-custodial measures.

States should end all administrative or preventive detention of children and instead develop alternatives to deprivation of liberty, including diversion programmes, care, guidance and supervision orders, counseling, probation, foster care, education and vocational training programmes, and other non-custodial measures.

![]() States should ensure that any sentence for national security offenses is appropriate to the child’s age and aimed at their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

States should ensure that any sentence for national security offenses is appropriate to the child’s age and aimed at their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

![]() States should take all necessary measures to ensure that rehabilitation programmes are neither punitive nor discriminatory and do not amount to arbitrary detention.

States should take all necessary measures to ensure that rehabilitation programmes are neither punitive nor discriminatory and do not amount to arbitrary detention.

![]() States should take responsibility for children abroad who are their citizens and who may be detained on security related offenses or for association with armed groups, including children born to their nationals.

States should take responsibility for children abroad who are their citizens and who may be detained on security related offenses or for association with armed groups, including children born to their nationals.

![]() States should not use counter-terrorism powers to prosecute foreign children for the unlawful presence or illegal entry into a State, particularly when they have travelled to the country with their families or have been born in the country.

States should not use counter-terrorism powers to prosecute foreign children for the unlawful presence or illegal entry into a State, particularly when they have travelled to the country with their families or have been born in the country.