Child Participation

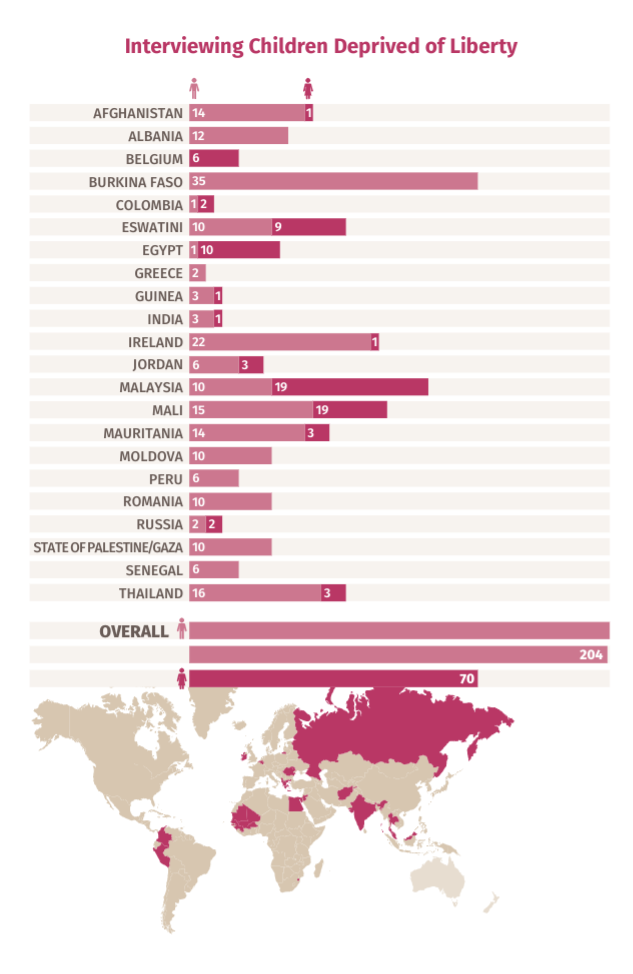

The research team – with unique expertise in children’s participation methodologies and international children’s rights law – partnered with Terre des Hommes and a range of international NGOs to access and collate the views and experiences of

274 children from 22 countries

across a range of detention settings. The process was not and did not purport to be representative of the views of all children in detention around the world. However, it was nonetheless an important step in ensuring that the views, perspectives and experiences of children deprived of their liberty were taken into account in the Global Study.

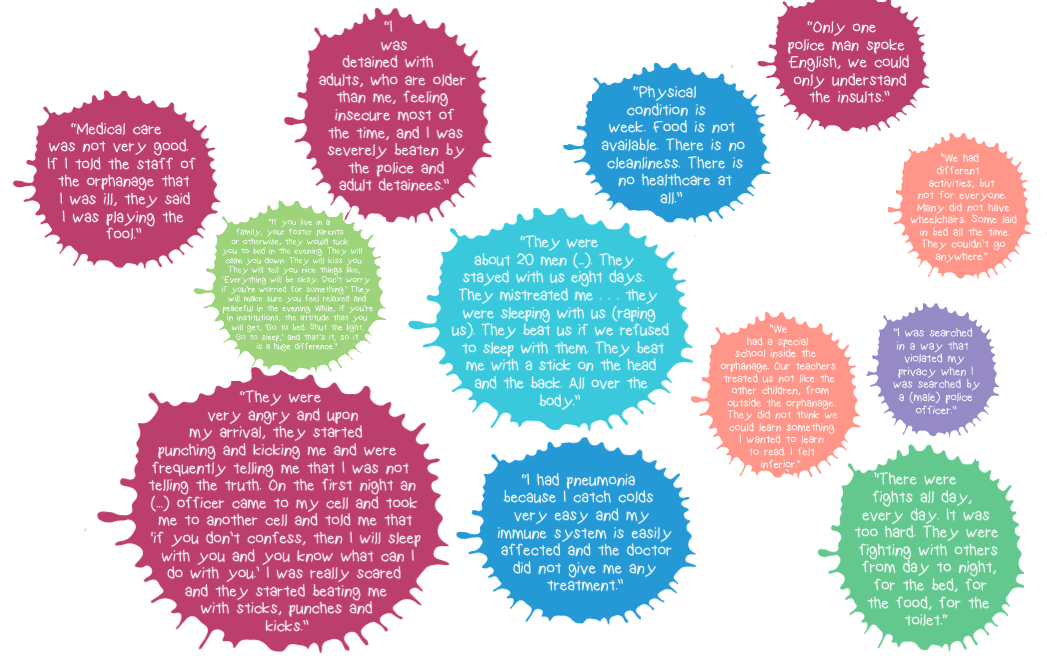

The overview of children’s reported experiences of their rights in detention

Most of the children interviewed were living in institutions or in immigration detention, but the following list of conditions was also confirmed by those detained in police stations. During the consultation process, children reported about:

- The lack of protection of their rights;

- Poor health care;

- Overcrowding;

- Poor food quality;

- Unhygienic living conditions;

- Inadequate access to education and leisure;

- Exclusion from the decision-making process about their own fate;

- Being denied access to information, or informed in a way that they could not understand;

- Feelings of isolation, loneliness and fear;

- Being subjected to violence or ill-treatment;

- Being placed with adults who were detained for criminal activities, such as drug dealers, thieves or people who had committed murder;

- Feeling discrimination and stigma connected to different factors including ethnicity, economic status, (dis)ability, sex or sexual orientation.

Cross-cutting themes emerged from consultations

Fear, Isolation, Harm and Trauma

A key theme across a significant number of the consultation responses was isolation and fear. This was most evident in accounts of the early stages of detention and pre-detention, and the hostile environment of detention in police stations where children were often unable to associate with others and/or had to wait for long periods without information. A significant number of children reported feelings of isolation and loneliness in detention, particularly in pre-detention or in police stations. One young woman in a child justice institution was feeling this acutely at the time of the consultation as all the other girls had been released three months previously.

In spite of the serious nature of the threats around them, some of the children showed resilience and an ability to adapt to the adverse circumstances in which they found themselves.

While remaining vulnerable to the risks and harms associated with detention, some participants described processes that helped them tolerate the negative effects of stress and conflict. They identified the need for social and other support mechanisms associated with successful adjustment that also enabled them to avoid reoffending.

Coping with Adversity

Disempowerment

The feeling of being disempowered, by systems and by individuals in the system, emerged in many of the responses of the children who participated in the research. A recurring theme was the way in which complicated legal language obscured their understanding of what was happening to them.

Children described their experiences of discrimination and stigma as connected to different factors including ethnicity, economic status, (dis)ability, sex or sexual orientation. One group of children discussed how sentences for children were too harsh in general, and that these varied depending on the ethnicity of the young person, the duration of detention – on economic status of the family, as well as differential treatment on the basis of their disability.

Discrimination and Stigma

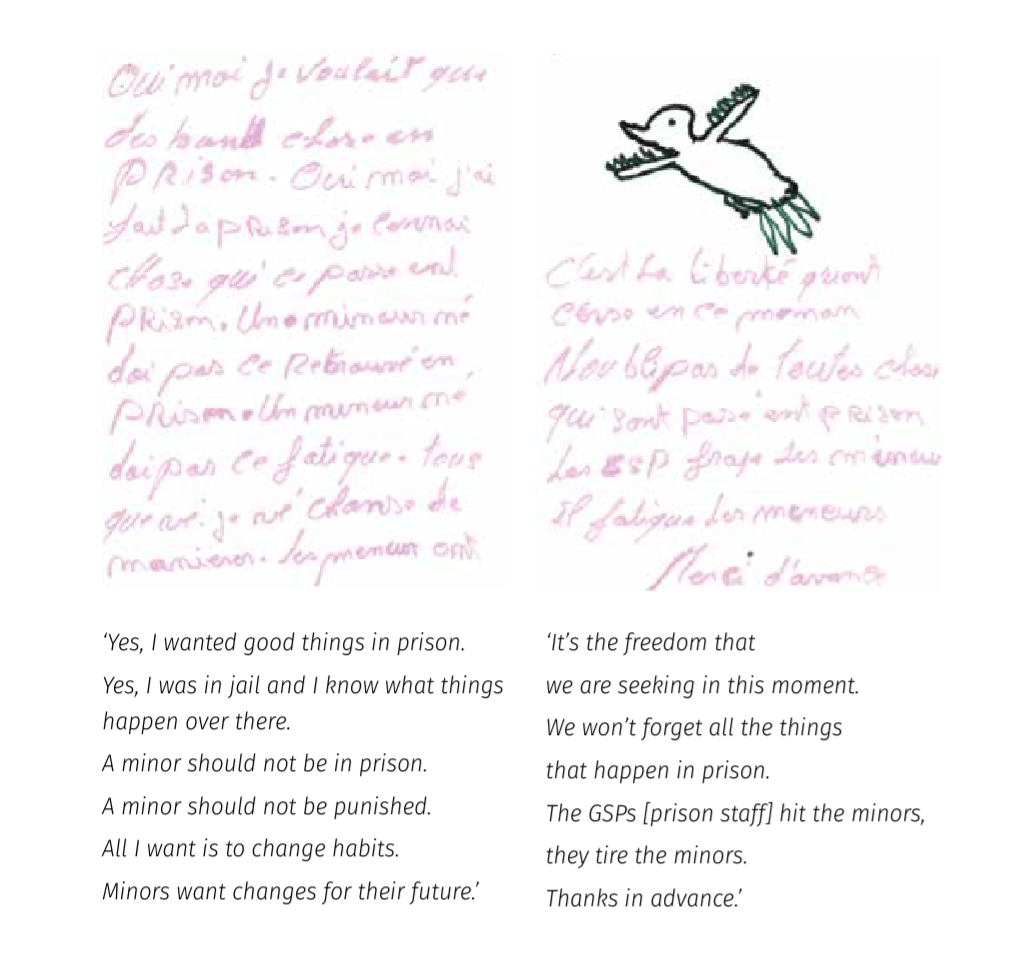

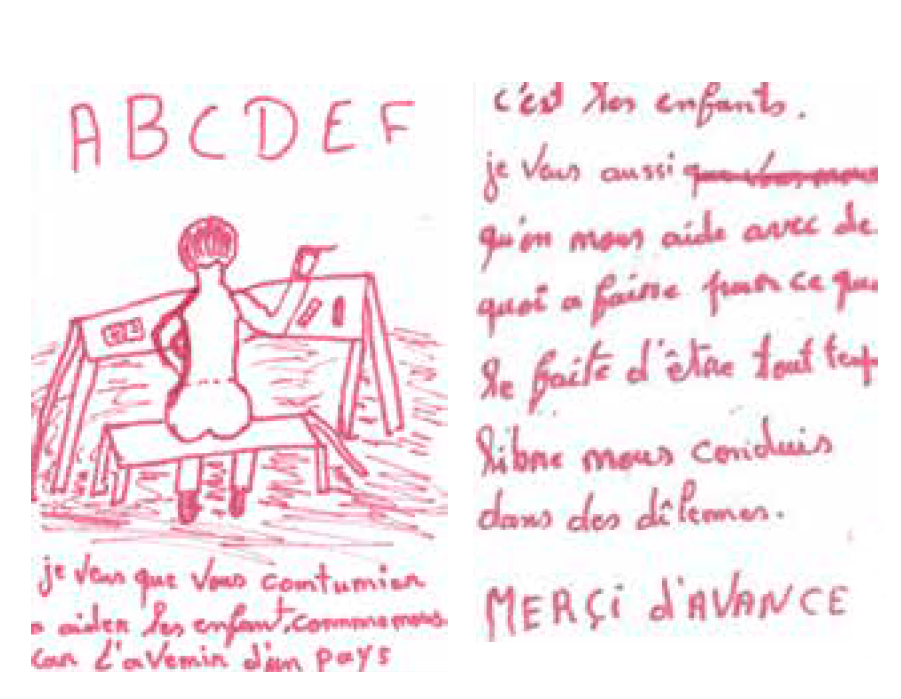

Aspirations for Future

Many children had positive aspirations for a future beyond detention, where they would reunite with their families and friends and enjoy life as independent human beings contributing to their communities. They saw education and skills development as integral to their reintegration and to achieving a better life once they would be released. Almost all children in justice institutions confirmed that they had access to some form of education or training programme, with courses ranging from literacy to social development programmes or vocational training (e.g. plumbing, computing, hairdressing). The fact of not mentioning in their certificates that they graduated in correctional services was also raised as very important.

Children also shared experiences of resilience and hope and highlighted the importance of friendships with peers and adults whom they could trust, such as social workers, who were working in their best interests. Irrespective of the setting, children almost always focused on the need for community or family-based care as an alternative to detention. Some suggestions included having house arrest or being hosted in a shelter with support services.