Migration

Main Findings

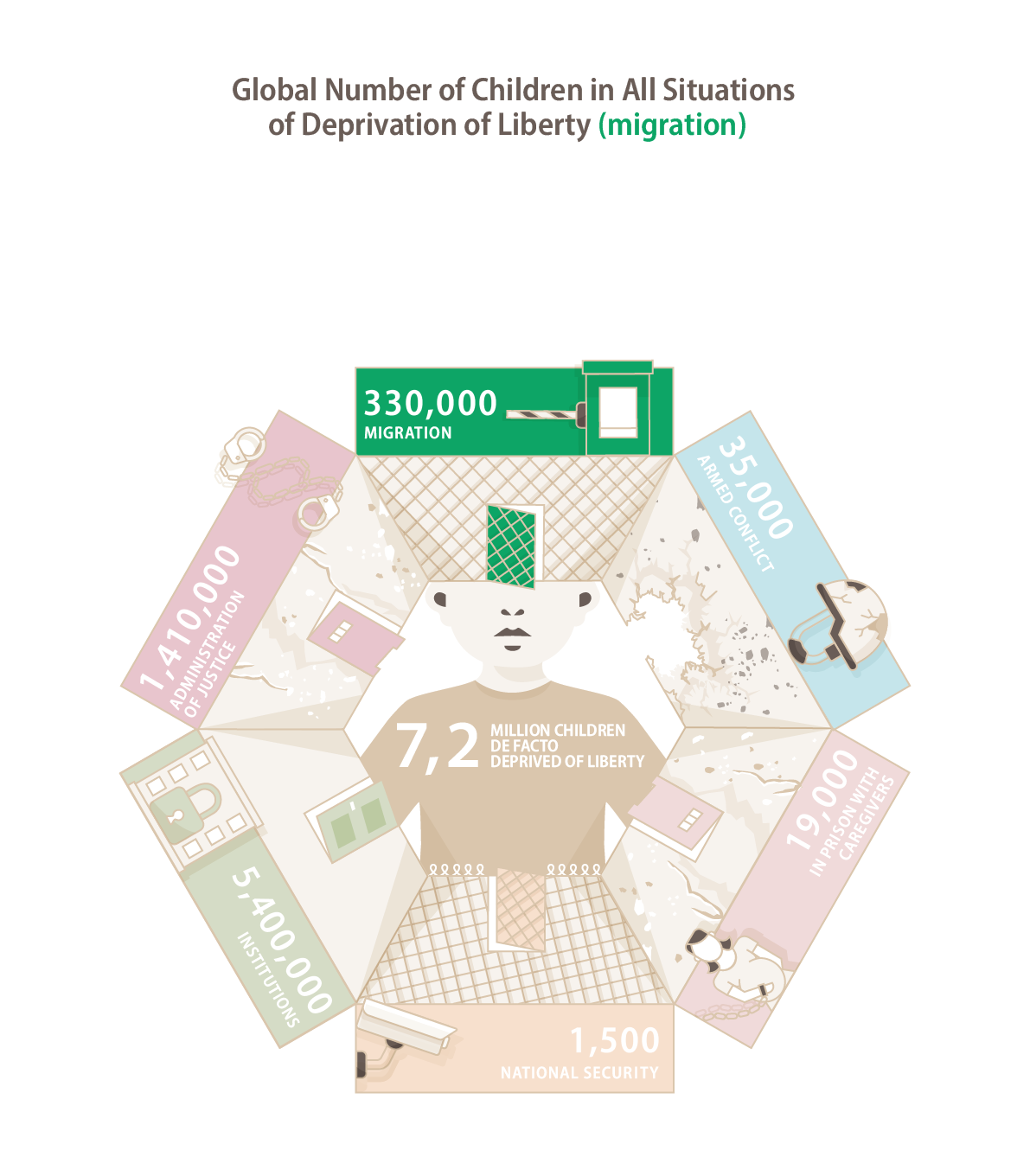

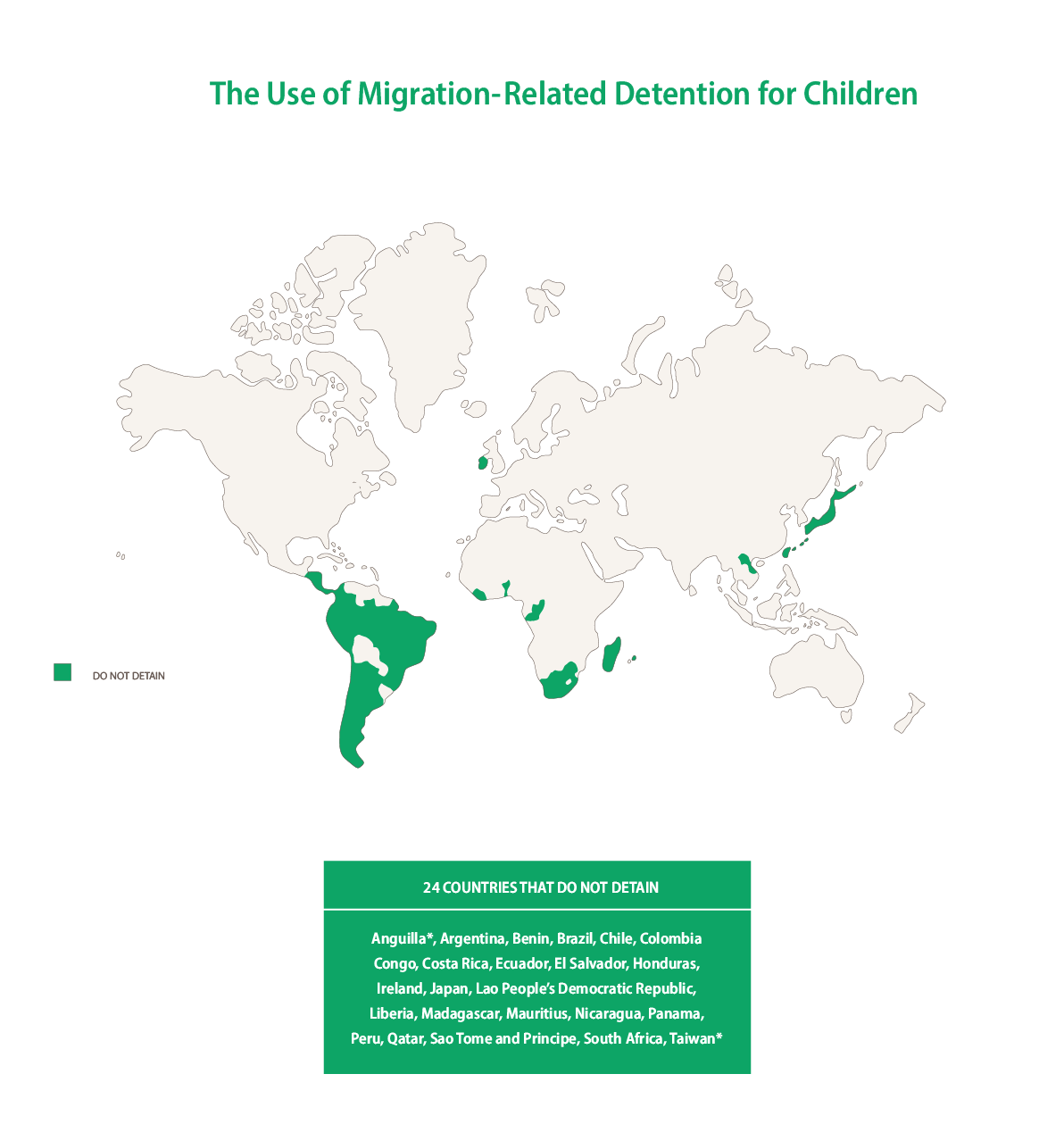

![]() At least 330,000 children are detained for migration-related purposes per year around the world. At least 80 States are known to still detain children for such reasons, while at least 24 States do not or claim not to do so.

At least 330,000 children are detained for migration-related purposes per year around the world. At least 80 States are known to still detain children for such reasons, while at least 24 States do not or claim not to do so.

![]() According to a publication from 2021 prepared by UNICEF, among the world’s migrants are nearly 34 million refugees and asylum seekers who have been forcibly displaced from their own countries – half of them children. In 2020, the number of international migrants reached 281 million; 36 million of them were children.

According to a publication from 2021 prepared by UNICEF, among the world’s migrants are nearly 34 million refugees and asylum seekers who have been forcibly displaced from their own countries – half of them children. In 2020, the number of international migrants reached 281 million; 36 million of them were children.

![]() Immigration detention frequently subjects children to deplorable conditions due to overcrowding, inappropriate food, insufficient access to drinking water, unsanitary conditions, lack of adequate medical attention, and irregular access to washing and sanitary facilities and to hygiene products, lack of appropriate accommodation and other basic necessities. Immigration detention is harmful to a child’s physical and mental health, aggravating existing health conditions and causing new ones to arise, including anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Some of the stresses causing mental harm are related to the context of detention (such as locked gates and constant supervision by detention officers), or they are related to the uncertainty of waiting for visa decisions and having pre-existing cases of trauma. It furthermore exposes the child to the risk of sexual abuse and exploitation.

Immigration detention frequently subjects children to deplorable conditions due to overcrowding, inappropriate food, insufficient access to drinking water, unsanitary conditions, lack of adequate medical attention, and irregular access to washing and sanitary facilities and to hygiene products, lack of appropriate accommodation and other basic necessities. Immigration detention is harmful to a child’s physical and mental health, aggravating existing health conditions and causing new ones to arise, including anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Some of the stresses causing mental harm are related to the context of detention (such as locked gates and constant supervision by detention officers), or they are related to the uncertainty of waiting for visa decisions and having pre-existing cases of trauma. It furthermore exposes the child to the risk of sexual abuse and exploitation.

Legal Background

The Global Study, along with other UN bodies and agencies, such as the UN Secretary-General, the CRC Committee, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, UNHCR, IOM or UNICEF, reconfirms that there are always non-custodial solutions available, which States must resort to in order to avoid the detention of children. This applies equally to unaccompanied and separated children and children who migrate with their parents.

![]() Migration-related detention of children, therefore, always violates Article 37(b) CRC.

Migration-related detention of children, therefore, always violates Article 37(b) CRC.

![]() In addition, it is difficult to reconcile with the principle of the best interests of the child in Article 3 CRC. Therefore, States have a legal obligation to prohibit migration related detention of children and to make proper non-custodial alternatives available to migrant children.

In addition, it is difficult to reconcile with the principle of the best interests of the child in Article 3 CRC. Therefore, States have a legal obligation to prohibit migration related detention of children and to make proper non-custodial alternatives available to migrant children.

![]() If children migrate with their families, such non-custodial facilities must also be made available to their families to avoid the separation of such children from their families, contrary to Article 9 CRC.

If children migrate with their families, such non-custodial facilities must also be made available to their families to avoid the separation of such children from their families, contrary to Article 9 CRC.

Pathways to Detention

States detaining children on the basis of their migration status offer multiple justifications:

![]() health and security screening,

health and security screening,

![]() identity verification,

identity verification,

![]() age assessment,

age assessment,

![]() illegal entry,

illegal entry,

![]() facilitation of deportation,

facilitation of deportation,

![]() fear of children absconding.

fear of children absconding.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() Since migration-related detention of children cannot be considered as a measure of last resort and is never in the best interests of the child, it always violates Article 3 and Article 37(b) of the CRC. It should, therefore, be explicitly prohibited and abolished by domestic law.

Since migration-related detention of children cannot be considered as a measure of last resort and is never in the best interests of the child, it always violates Article 3 and Article 37(b) of the CRC. It should, therefore, be explicitly prohibited and abolished by domestic law.

![]() States should refrain from criminalising irregular entry or stay and eradicate any form of immigration detention.

States should refrain from criminalising irregular entry or stay and eradicate any form of immigration detention.

![]() States should assess on a case-by-case basis what non-custodial, community-based solutions are most appropriate for the protection and care of migrant children.

States should assess on a case-by-case basis what non-custodial, community-based solutions are most appropriate for the protection and care of migrant children.

![]() Unaccompanied and separated children should be referred to the regular domestic child protection system for appropriate attention, protection, and care.

Unaccompanied and separated children should be referred to the regular domestic child protection system for appropriate attention, protection, and care.

![]() Children with family members should be allowed to remain with their families in non-custodial contexts while their immigration status is resolved and the children’s best interests are assessed.

Children with family members should be allowed to remain with their families in non-custodial contexts while their immigration status is resolved and the children’s best interests are assessed.

![]() Non-custodial measures should ensure access to information about the process, legal assistance, health, housing, access to education and other services, as well as appropriate case management, regular check-ins by social workers and social support.

Non-custodial measures should ensure access to information about the process, legal assistance, health, housing, access to education and other services, as well as appropriate case management, regular check-ins by social workers and social support.

![]() States should only use age assessment procedures where there are grounds for serious doubt about an individual’s age.

States should only use age assessment procedures where there are grounds for serious doubt about an individual’s age.

![]() States should only return children to their countries of origin or last residence, or transfer children to a third country, based on a determination that such return is in the individual child’s best interests undertaken by a child protection or child welfare authority.

States should only return children to their countries of origin or last residence, or transfer children to a third country, based on a determination that such return is in the individual child’s best interests undertaken by a child protection or child welfare authority.

![]() Authorities should take steps to ensure children and families have access to justice and effective remedies, including through administrative sanctions and prosecution as warranted, when their rights to liberty and family life are violated.

Authorities should take steps to ensure children and families have access to justice and effective remedies, including through administrative sanctions and prosecution as warranted, when their rights to liberty and family life are violated.

![]() States should ensure regular access by legal representatives, national and international monitoring bodies, and civil society organisations to all places of immigration detention.

States should ensure regular access by legal representatives, national and international monitoring bodies, and civil society organisations to all places of immigration detention.