Administration of Justice

Main Findings

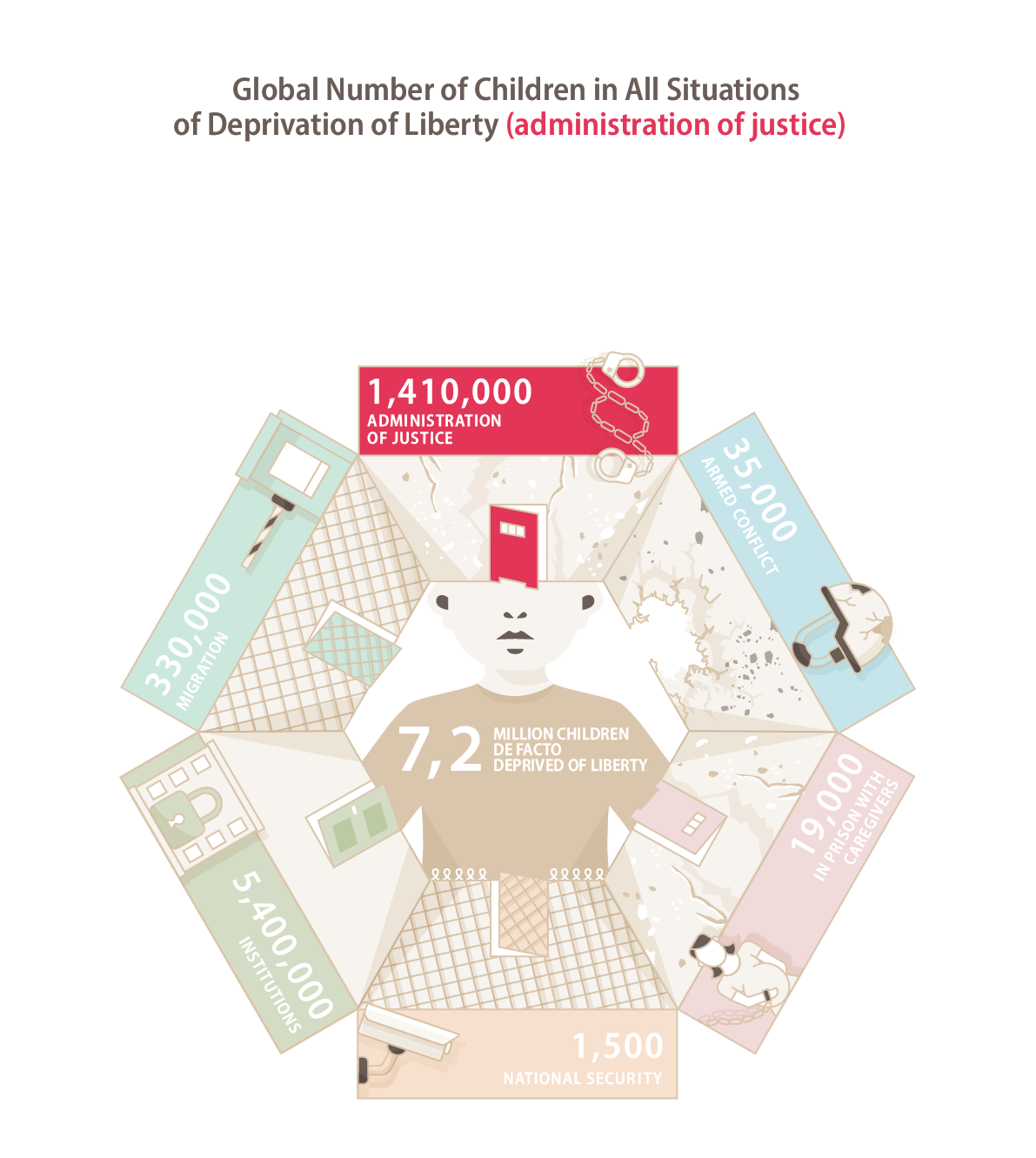

At least 410,000 children are deprived of liberty in pre-trial detention facilities and prisons per year. In addition, roughly 1 million children are estimated to be held in police custody every year.

In many countries, the imprisonment of children is based on a punitive approach and is not primarily aimed at the rehabilitation and reintegration of children into society, as required by international law. Detention in the context of the administration of justice is still widely overused and can, in most cases, not be justified as a measure of last resort, as required by the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In many countries, corruption and the lack of adequate human and financial resources in the administration of justice lead to an excessive length of criminal proceedings and duration of detention, contributing greatly to an excessive scope of traumatic experiences for children.

Conditions in detention are unacceptably poor in the great majority of countries, including:

![]() overcrowding;

overcrowding;

![]() lack of separation between children and adults, girls and boys;

lack of separation between children and adults, girls and boys;

![]() systemic invasion of privacy;

systemic invasion of privacy;

![]() lack of psychological support for the child, including contact with his/her family and the outside world;

lack of psychological support for the child, including contact with his/her family and the outside world;

![]() insufficient access to education, healthcare, recreational and cultural activities;

insufficient access to education, healthcare, recreational and cultural activities;

![]() lack of child-sensitive procedures and access to information;

lack of child-sensitive procedures and access to information;

![]() alarmingly high level of violence, exhibited through regular corporal punishment, which has detrimental impacts on the wellbeing and mental health of children.

alarmingly high level of violence, exhibited through regular corporal punishment, which has detrimental impacts on the wellbeing and mental health of children.

Legal Background

![]() Under Article 9 ICCPR, everyone has the right to personal liberty and security.

Under Article 9 ICCPR, everyone has the right to personal liberty and security.

![]() Article 37(b) CRC reiterates this right for all children but requires as an important further restriction that the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child must be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

Article 37(b) CRC reiterates this right for all children but requires as an important further restriction that the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child must be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

![]() In this respect, Article 40(4) CRC provides that a “variety of dispositions, such as care, guidance and supervision orders; counselling; probation; foster care; education and vocational training programmes and other alternatives to institutional care shall be available…”

In this respect, Article 40(4) CRC provides that a “variety of dispositions, such as care, guidance and supervision orders; counselling; probation; foster care; education and vocational training programmes and other alternatives to institutional care shall be available…”

![]() The arrest and police custody of a child must be used only for the shortest appropriate period of time, not lasting longer than 24 hours, as recommended by the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

The arrest and police custody of a child must be used only for the shortest appropriate period of time, not lasting longer than 24 hours, as recommended by the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

![]() Regarding imprisonment after trial, the UN Minimum Standards and Norms on Juvenile Justice, also known as Beijing Rules, establish that deprivation of liberty shall not be imposed unless the child “is adjudicated of a serious act involving violence against another person or of persistence in committing other serious offences and unless there is no other appropriate response”.

Regarding imprisonment after trial, the UN Minimum Standards and Norms on Juvenile Justice, also known as Beijing Rules, establish that deprivation of liberty shall not be imposed unless the child “is adjudicated of a serious act involving violence against another person or of persistence in committing other serious offences and unless there is no other appropriate response”.

Furthermore, life imprisonment without the possibility of release or parole is explicitly prohibited by the Convention of the Rights of the Child, and since the imprisonment of a child shall be used only for the shortest appropriate period of time, a strict proportionality test is required for any prison sentence of a child, which shall prevent any excessive prison sentences.

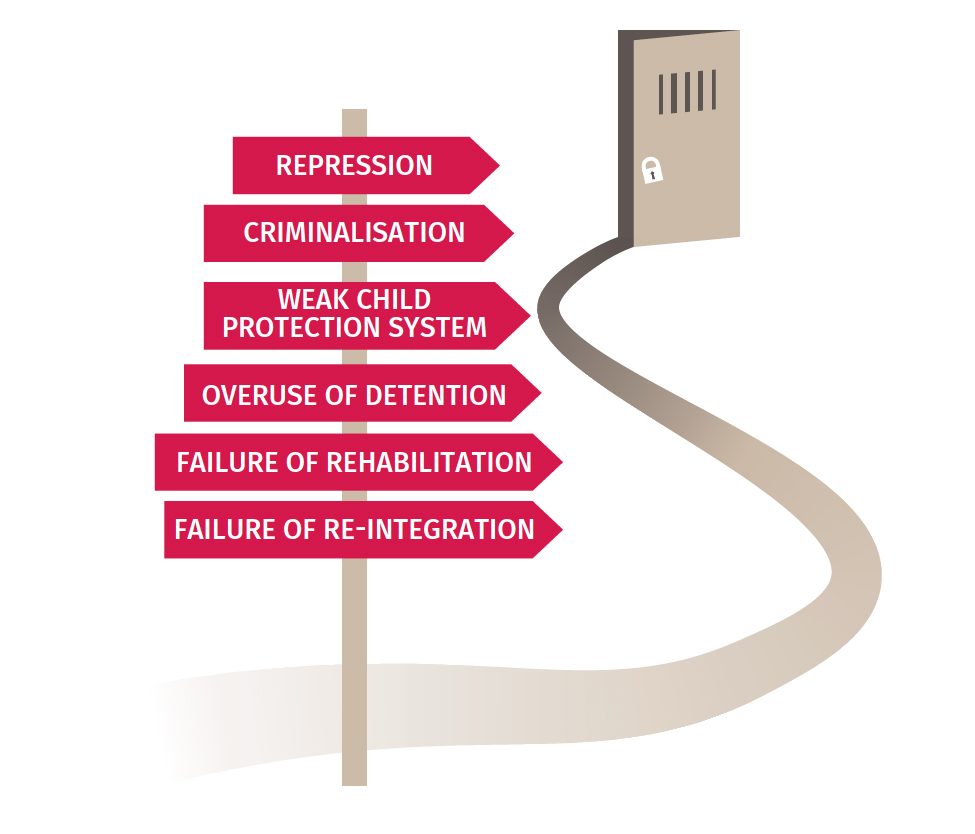

Pathways to Detention

![]() REPRESSION

REPRESSION

Discrimination in the justice system is widespread and leads to a large overrepresentation of some children in detention settings and throughout judicial proceedings, such as children living or working on the street, children from poor and socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, from migrant and indigenous communities, ethnic and religious minorities and the LGBTI community, as well as children with disabilities and, above all, boys.

![]() CRIMINALISATION

CRIMINALISATION

Negative attitudes in society towards children in conflict with the law and a punitive approach called for by the media, politicians and policymakers to tackling child offending are often the main reason for the introduction of repressive legislation and excessive criminalisation. This usually does not have the desired deterrent effect but leads instead to a vicious circle of increasing violence on the part of law enforcement officials as well as youth gangs.

![]() WEAK CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEM

WEAK CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEM

Child protection systems shall ensure that the behaviour of children can be dealt with outside the criminal justice system and by avoiding deprivation of liberty in institutions.

![]() OVERUSE OF DETENTION

OVERUSE OF DETENTION

Excessive criminalisation of so-called ‘status offences’ (such as truancy, running away from home, disobedience, underage drinking, curfew violations, consensual sexual activity between teenagers, ‘disruptive’ behaviours and practices against traditions and morality) criminalises conduct that only applies to young people, not to adults. If the application of ‘status offences’ leads to detention and imprisonment of children, this cannot be considered as a measure of last resort and, therefore, violates the CRC.

![]() FAILURE OF REHABILITATION

FAILURE OF REHABILITATION

The lack of investment in prevention and overreliance on child detention are exacerbated by negative attitudes towards children in the justice system that call for more retributive and tougher responses to children who commit crimes. Without offering appropriate protection systems, rehabilitation and reintegration programmes, these children are also more likely to be stuck in the vicious circle of re-offending leading them back to detention.

![]() FAILURE OF REINTEGRATION

FAILURE OF REINTEGRATION

Law enforcement agencies, the judiciary, local authorities, health, education and social services, child welfare agencies and other State institutions are expected to function together to create and maintain a protective and enabling environment for children and to ensure support for their families. The lack of efficient coordination and cooperation between these different actors results in conflicting goals and undermines the overall functioning of the child justice process.

Promising Practices

Recommendations

![]() Decriminalise the behaviour of children.

Decriminalise the behaviour of children.

![]() Establish specialised child justice systems with special children’s courts, judges, prosecutors, police officers and other law enforcement personnel undergoing special training on the rights and needs of children.

Establish specialised child justice systems with special children’s courts, judges, prosecutors, police officers and other law enforcement personnel undergoing special training on the rights and needs of children.

![]() Apply diversion at every stage of the criminal justice proceedings.

Apply diversion at every stage of the criminal justice proceedings.

![]() Tackle the root causes of crimes committed by children by strengthening parental support, providing assistance to dysfunctional families, etc.

Tackle the root causes of crimes committed by children by strengthening parental support, providing assistance to dysfunctional families, etc.

![]() Ensure strict time limits for the detention of children at the stages of police custody (never longer than 24 hours), pre-trial detention (never longer than 30 days until formal charges are laid) and detention pending trial (with a maximum of six months between the initial date of detention and the final decision on the charges).

Ensure strict time limits for the detention of children at the stages of police custody (never longer than 24 hours), pre-trial detention (never longer than 30 days until formal charges are laid) and detention pending trial (with a maximum of six months between the initial date of detention and the final decision on the charges).

![]() Ensure that children at all stages of the criminal justice process have access to effective procedural safeguards and complaints mechanisms, are properly informed, have access to their families, lawyers, doctors and interpreters, are provided with free legal aid and assistance, are brought promptly after their arrest before an independent judge, and are guaranteed their right to be heard in all decisions concerning them so that their views are given due weight.

Ensure that children at all stages of the criminal justice process have access to effective procedural safeguards and complaints mechanisms, are properly informed, have access to their families, lawyers, doctors and interpreters, are provided with free legal aid and assistance, are brought promptly after their arrest before an independent judge, and are guaranteed their right to be heard in all decisions concerning them so that their views are given due weight.

![]() Develop an effective system of independent and unannounced monitoring of all places of detention of children in the criminal justice system.

Develop an effective system of independent and unannounced monitoring of all places of detention of children in the criminal justice system.

![]() Ensure that children deprived of liberty in the criminal justice system are treated with humanity and respect for their inherent dignity, receive appropriate care and treatment in relation to their needs, maintain regular contact with their families and friends, and enjoy all other human rights.

Ensure that children deprived of liberty in the criminal justice system are treated with humanity and respect for their inherent dignity, receive appropriate care and treatment in relation to their needs, maintain regular contact with their families and friends, and enjoy all other human rights.

![]() Prohibit and punish all forms of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including corporal punishment, physical or psychological violence or solitary confinement as means of discipline.

Prohibit and punish all forms of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including corporal punishment, physical or psychological violence or solitary confinement as means of discipline.

![]() Make widely available measures such as early release and post-release programmes, including mentoring programmes, community service work and group/ family conferencing.

Make widely available measures such as early release and post-release programmes, including mentoring programmes, community service work and group/ family conferencing.