Health

Deprivation of liberty may negatively impact children’s health for two key reasons:

- Deprivation of liberty is an inherently distressing, potentially traumatic experience and, as such, may have adverse impacts on mental health.

- The particular circumstances in which children are deprived of liberty may be harmful to their health, including exposure to unsanitary conditions increasing the risk of infection, a concentration of people with infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis and HIV), restrictions on movement and physical activity adversely impacting physical development and increasing the risk of obesity, and inadequate diet. Healthcare in places of deprivation of liberty remains a great issue due to limitations of the research on this topic.

Different situations of deprivation of liberty can have various impacts on children's health:

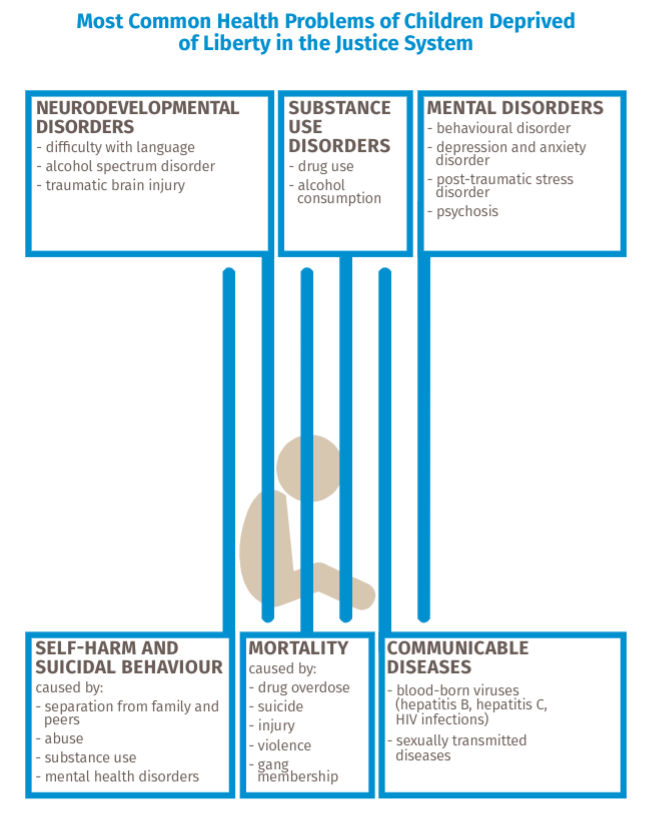

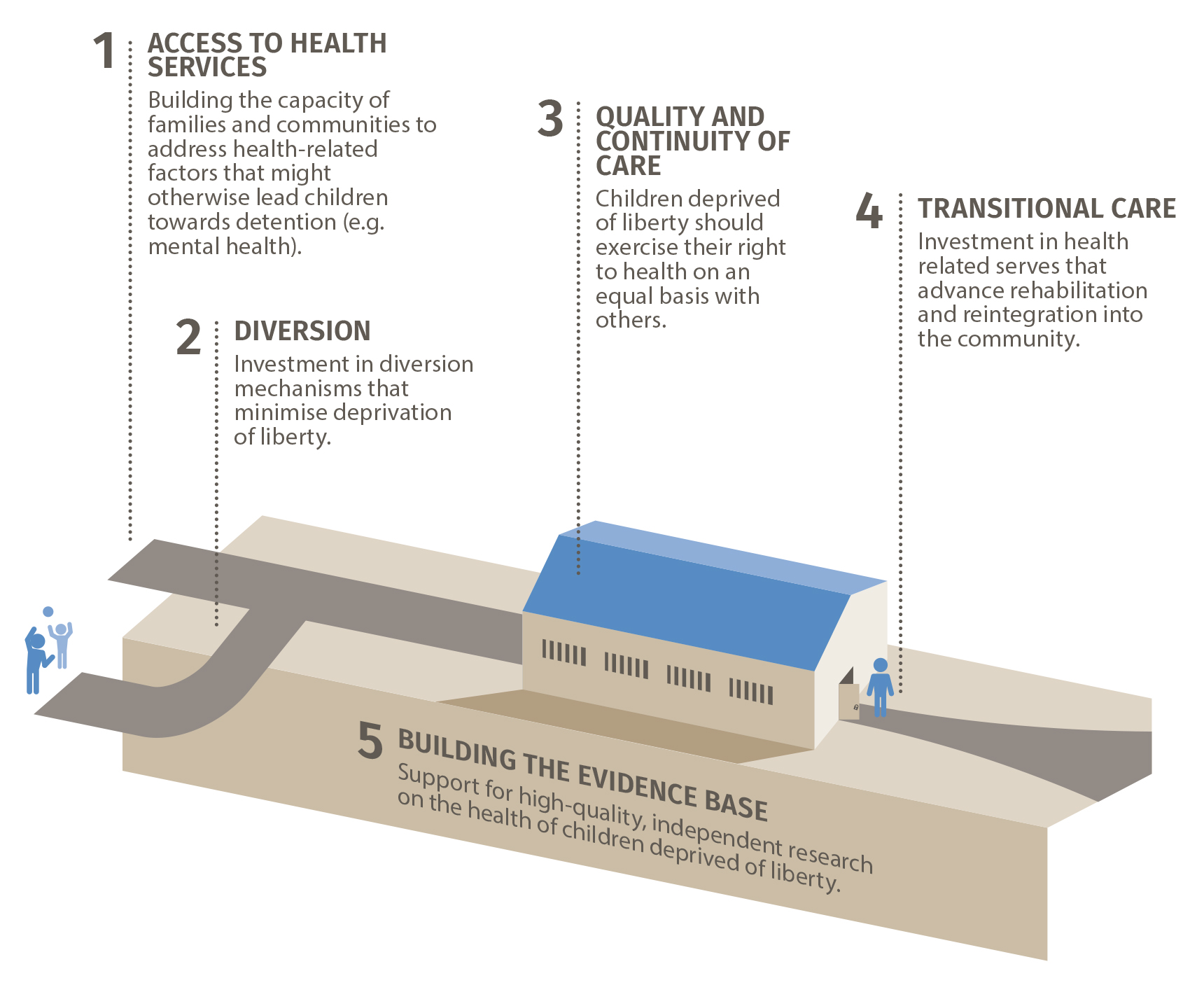

In administration of justice, complex and often co-occurring health conditions include mental disorder, depression, cognitive dysfunction and learning difficulties, sexually transmitted and blood-borne viral infections, self-harm and suicidal behaviour, oral disease, and chronic conditions such as asthma. Further, health-compromising behaviours such as substance use, sexual experiences and violence contribute to a poorer health profile. However, even where children are in justice-related detention, potentially positive health outcomes, contingent on the quality of care, include the delivery of overdue vaccinations, diagnosis and treatment of communicable diseases, and addressing social determinants of health through education and linkage to housing services on release.

Children in immigration detention often come from settings characterised by civil and political unrest or war and may experience inadequate nutrition, limited access to appropriate healthcare, or exposure to environmental risk factors. Mental health problems, like development delays, depression, anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and self-harm, may arise from experiences of trauma in the home country or during the arduous journey to immigration detention, including torture and trauma prior to arrival, the breakdown of families within detention, the length of detention and uncertainties about outcomes, and witnessing trauma within detention.

In cases where children’s primary caregivers are incarcerated, strong evidence suggests that children are at increased risk of a range of poor health outcomes, including poorer oral and mental health, exposure to communicable diseases, malnutrition, behavioural problems, as well as below average cognitive and language development. However, allowing babies and small children to remain with their incarcerated mother permits breastfeeding and promotes secure attachment between mother and child, which is thought to be mutually beneficial. The health impact on a child living with their primary caregiver in prison generally highly depends on contextual factors and detention conditions.

In the context of armed conflict or national security, children may have experienced significant trauma, been injured in conflict, and suffered from disruption to healthcare and other services. Case studies in Central America and Southeast Asia indicate that torture of children detained in the context of armed conflict or national security may result in long-term problems in cognition, disrupted sleep, apathy, helplessness, behavioural changes including aggression, and ongoing pain.

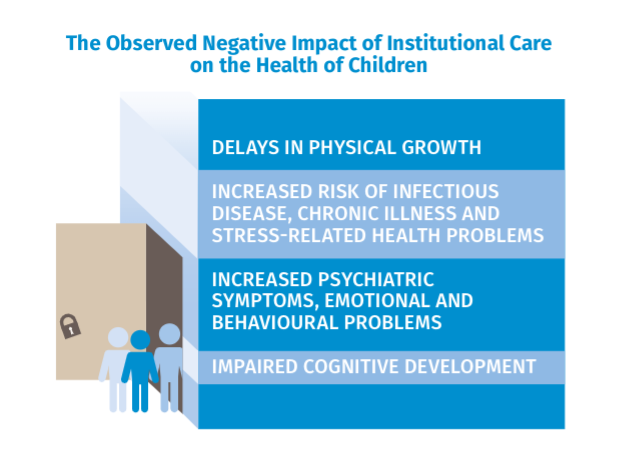

Institutionalisation of children – particularly during critical developmental periods – is associated with adverse impacts on physical health and development, mental health, and cognitive development. As concerns physical health, studies have found institutionalised children to show significant delays in physical growth in high-income countries, and an increased risk of infectious diseases. A greater prevalence of psychiatric symptoms including hyperactivity and inattention, internalising and externalising disorders, substance misuse, depression, and suicidality, have been associated with early institutionalisation. In addition, children in residential or foster care are at increased risk of child maltreatment and abuse, potentially contributing to long-standing emotional, behavioural, and learning difficulties. Delays in cognitive development and specific learning difficulties have further been associated with severe institutional neglect. However, the quality of care is of primary importance, rather than the fact of institutionalisation per se.